Woman as Communion by Megan McDermott

Review by Reyzl Grace

Game Over Books, 2022

::

So much of this little volume—the second chapbook from poet and Episcopal priest Megan McDermott—is about accompaniment, and I do not doubt that many fine reviews will follow it like Peter and Andrew leaving their father’s boat. Its author, after all, has appeared in The Christian Century and other prestigious publications where her coreligionists will not fail to take note of this new offering. After I had spent an hour with it, though, in which I found myself following McDermott’s vision like Ruth pursuing Naomi, I felt a need to bear witness to it for those who, like myself, do not share its author’s faith. Not least among the small miracles of this book is that, far from hiding womanhood beneath the Eucharist, so as to make its significance opaque outside the church, it provides an opening into the Eucharist through womanhood—not to lead us to the altar table, but to allow us to turn back into our own lives and traditions to see anew, and perhaps appreciate more deeply, what lies nearest our hearts, precisely for having learned to glimpse it, however fleetingly, in an unfamiliar guise. Were I a Christian, I might call it the gift of tongues.

As a Jew, I will instead call it an act of courage. In only the second poem, McDermott commits herself to a very Semitic recognition that the personal is salvational, determined to follow the many meanings of the word with, “despite how preferable it might feel to journey / alone, feigning detachment from matter / and pain and every broken woman before me.” We have all seen stories in the paper about declining religious affiliation, declining union membership, declining civic participation. As the weight of the accumulated mistakes of centuries crushes down on us with ever greater force and speed, it is so tempting to “feign detachment,” and it is a temptation to which Christian tradition can sometimes be especially liable, with its tendency to read all things as signs and foreshadowings. McDermott resists this temptation, however, and it shows in her treatment of Eve, of Hannah, of Rachel, Bathsheba, and Naomi. All find their place—some inked more boldly by details supplied from the author’s imagination, some traced onto new settings and situations, but always sketched faithfully to the uncertainty and imperfection they possess in Hebrew scripture.

It is this commitment to the desperate humanity of the figures of the Abrahamic tradition that opens Woman as Communion in two complementary directions. Much of the book extends an invitation to Jews, Muslims, Bahá’ís, and anyone who, observant or not, has cultural roots in the stories; for such readers, the richness with which these figures are portrayed offers fresh perspectives on McDermott’s themes. “To Adam” (which you can read online), for example, is an address in Eve’s voice to her husband. In mainstream Christian tradition, Adam and Eve’s Fall has generally been portrayed as an act of rebellion—a choice to disobey God. In Islamic tradition, however, it has been presented as a case of forgetfulness—the command not to eat slipping carelessly from the first couple’s minds. Reading “To Adam” in the Christian tradition loads it with a sense of rejection and betrayal, making us witnesses to a well-justified rebuke and a lament over brokenness. To read it through an Islamic lens, on the other hand, might call to mind not so much betrayals as passions grown cold and carelessness with gifts taken for granted. The poem’s closing, then, might feel less final, and leave even a little more room for the hope it calls on the reader to find. What would happen if we read it steeped in Mormon exegesis, where the Fall is an act of Providence, orchestrated “that men might be . . . and . . . have joy” (2 Nephi 2:25)? Would it be still a third, distinct reading, or would it only call our attention more sharply to the tragedy of man’s forgetting—and particularly the intimate link between his forgetting of God and his forgetting of woman? Might we then not hear in Eve’s complaint, “You didn’t even call me by name,” the ferocity of forgetting as betrayal—the treble wound of McDermott’s simple line over sampled bass from Janelle Monae (another great American poet): “We gave you life, we gave you birth. / We gave you God, we gave you earth” (“Django Jane”)?

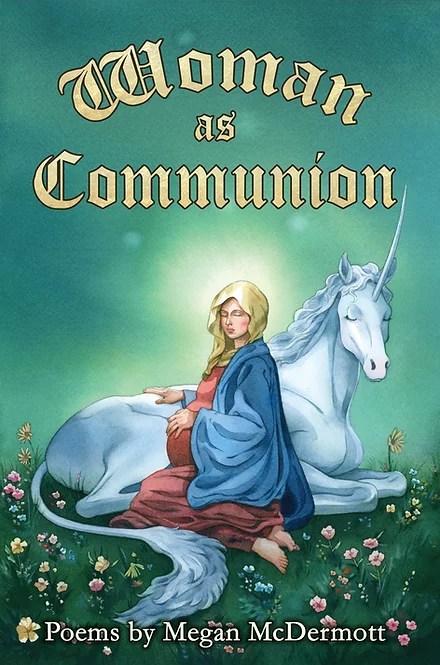

It is precisely by welcoming readers of many backgrounds into those kinds of conversations that McDermott is able to lead them on toward the book’s second opening, which is also its close. Just as the author’s reference to the Dutch mystic Hadewijch of Brabant makes us smile with the suspicion that some part of Julian of Norwich’s reflections on the “motherhood of Christ” has also been an influence (especially in “Today Christ Is”), the author’s brief mention of Simone Weil leaves me to wonder if I also detect a trace of Martin Buber, the Jewish existentialist who held that God emerges and resides in the space between “I and thou”—the opening created by a truly honest turning of the self toward another. I will not spoil the force of the sacrament for you, dear reader, and reduce it to a mere memorial feast by saying too much here. I only wish you to know that, when McDermott gathers Junia, Deborah, Mary, and Miriam around her on the last page, there is something in it that reminds me of seeing Jesus converse with Moses and Elijah on the mountain, and that, even if you have never darkened the door of a Christian church in your life and have no intention of doing so, this supremely gifted priest has found a way to communicate to you the achingly beautiful insight baked into the wafers—that, as the Protestant theologian Karl Barth put it, “God has chosen from eternity not to be without man”—and she has done it through the means right on the cover (by which you may, just this once, judge a book).

In “Some Obscure Fact”, McDermott writes about discovering the medieval symbolism of unicorns as signs of incarnation in a book about Hieronymous Bosch. “Art reminds me”, she reflects, “we lose / symbols all the time.” This book does only a little to restore to us the symbol of the unicorn, but it does a great deal to render back to us the symbol of woman, not in some pedestaled form, “smooth / and shut in the places where / another woman might tear” (“Divine C-Section”), but in the full figure of real, human life—messy, brutal, and fractured, but also beautiful, triumphant, and blessed. And because of this, it gives us back the symbol of woman not as a point of entry to some delimited facet of God as the “divine feminine” or to some particular mask that deity might wear as “the goddess,” but to the experience of the numinous in its divinely simple totality—the force that would knock us from our feet and sweep us clear of the tabernacle if someone did not teach us to see that there is more than one place where the tablets God has engraved on every human heart might be laid.

You can read this wonderful little book at your synagogue, in your mosque, or on the corner of Main Street—anywhere you might (perhaps for the first time) see the face of a woman, hear her story (even if it’s your own), and talk to God.

::

Reyzl Grace is a transfeminine Jewish poet, essayist, and storyteller working in both English and Yiddish, with writing to be found in So to Speak, the gamut mag, Crow & Cross Keys, Feminism & Religion, and elsewhere. She currently reads poetry for both Psaltery & Lyre and Cordella Magazine. You can find more of her work at her website, reyzlgrace.com, and by following her on Twitter @reyzlgrace.

Image description: Cover of Woman as Communion by Megan McDermott; the cover features a pregnant Mary figure with her hand on a white unicorn in a flower field.