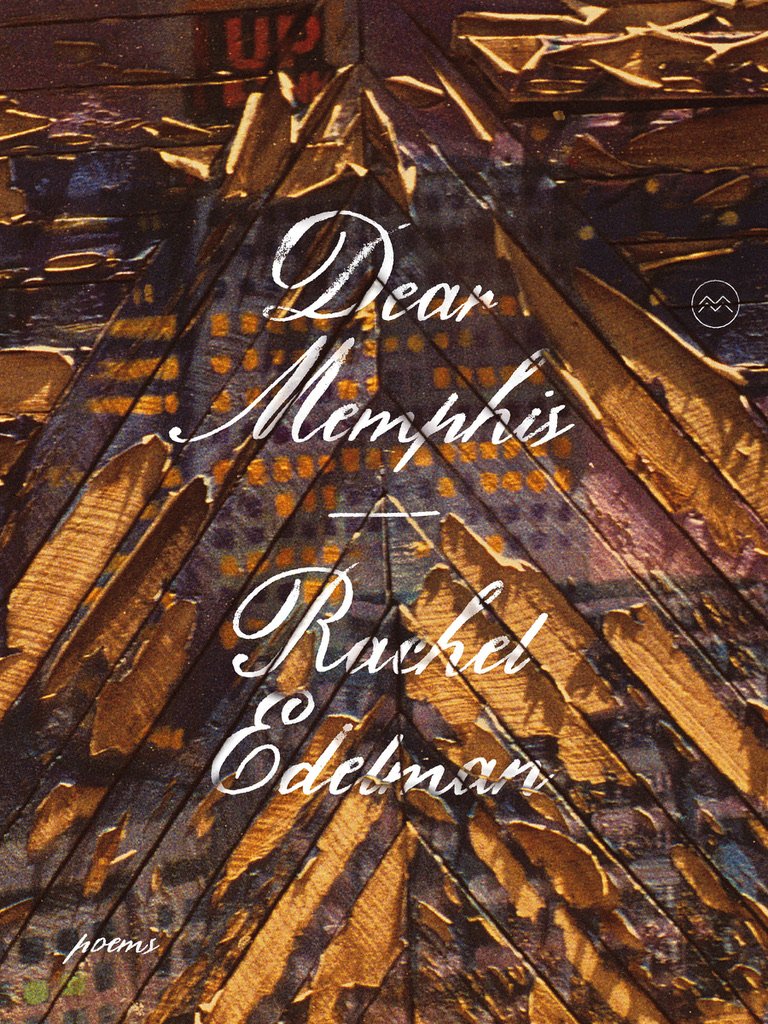

Dear Memphis by Rachel Edelman

River River Books, 2024

Review by Rebekah Wolman

::

One way into Rachel Edelman’s debut collection is to note the distinction between its comma-less title and “Dear Memphis,” —the title of each of the eleven epistolary poems scattered through the collection—and then to consider the role of those poems among the 43 that comprise the whole. A simple comma of direct address transforms the city of Edelman’s and her speaker’s birth from an apparent object of affection to an interlocutor, a confidante who seems to hold intimate knowledge of the speaker’s history and to whom she writes from a new home 2300 miles across the country. The city can be read as a jilted lover in some of the epistolary poems. In the book’s first poem, the speaker asks “who did I choose/when I wished myself elsewhere?” (“Return”), and the second “Dear Memphis,” poem begins with the question “Do you get jealous?” Is the collection, then, at least part extended love letter? Inasmuch as the most enduring love is often fraught with contradictions and complications, the answer may be yes, though certainly not a simple, unqualified yes.

Yet another entry point is the book’s epigraph from Kevin Young: “The past is a place / you cannot visit // but still—veiled—can see—. ” Edelman’s speaker visits the place of her and her family’s past and sees the past in that place quite clearly. Rather than obscuring her vision, the “veil” is more of a kaleidoscope lens, revealing the complexities and contradictions inherent in the place, its history, and the speaker’s relationship to both. Her challenge is not that she can’t go home again, but that she can’t completely leave home behind. Made “seasick” by the motion of a carwash in one “Dear Memphis,” poem, the speaker feels “… comfort // in a constant ache” and proclaims, “My restlessness doesn’t belong, yet here it lives // where somehow the suds/smell like your dust, // your most volatile fragments inside me.”

The first lines of the book’s long opening poem convey the same embodied sense of ambivalence about the past-place, immediately complicating the affection implied in the comma-less title:

Descent jumps and jostles,

nausea drops me

back to the floodplain

I fled.

Its first word implying generational as well as altitudinal descent, the line drops us into the many objects of the speaker’s ambivalence with its own hard landing. Anecdote and observational detail bring to life the themes of identity and otherness, segregation, ethnicity, religion, and race that freight the city’s history and the speaker’s history in it. A cab driver’s comment—“Do you have mixed blood?… You have an old world face” —makes the speaker’s “eyes flare.” Observing “On every corner, an alabaster cross”, the speaker recalls “parents [making] sure / we lived among / other mezuzahs.” The history of enslavement looms as “heat gleams // on shoulders screened CORRECTIONS: / workers in the cotton / still in chains.” Storefronts marked “AVAILABLE AVAILABLE… ” announce the decline of the local economy. Alluding to her connection to the land through its produce, the speaker refers to the tomatoes she buys at a farmers market as “the fat gold fruit / I was born to.” The paradox of coring those tomatoes “. . .knife plumb/to a warped board” troubles the intimacy implied in that description.

The speaker’s feelings about the city’s Jewish establishment and its apparent denial of racial tension emerges in an encounter with “the rabbi”, who beams

as he tells me how,

after King’s assassination,

The whole city sat shiva. No riots here.

My teeth tingle

with an anger he might not approve of.

And the speaker’s family’s long-time domestic helper, Minnie, is the subject of a full page in this first poem, their close and enduring relationship as apparent as the differences and inevitable distance between them: “We lean almost as close // as when we’d visit over the gospel radio.”

So many sources of the tension inherent in the speaker’s ambivalence —along with Edelman’s love of alliteration and its effect of insistence—are revealed in just the first poem’s six pages of spare, short lines with more white space than ink. The tension is sustained and developed throughout the collection in poems that are equally spare and vivid, preoccupied with diaspora and migration, past and present, general and personal, Jewish, North African, and African-American, in keeping with Edelman’s identification in the author bio as a poet “who writes into diasporic living.”

Several of the poems allude to the speaker’s and her family’s experience with anti-Semitism in the south. Her identity as a descendant of Jewish immigrants engenders compassion for and identification with other displaced people, but she also acknowledges her relative comfort. “The Boy on the Beach,” an elegy to a drowned migrant boy, draws parallels with her Jewish family’s history of persecution and flight in Europe but ends with the lines “We must be / safer than they were”.

In poem after poem, Edelman’s speaker implicates her inherited privilege and relative security, beginning with these lines in the first “Dear Memphis,” poem:

Memphis,

you remember

how our grandfather

would wing us out of any waiting room

when he walked in and said we were his.

“Where Else But Here”, a six-part ekphrastic poem in conversation with a viewing of Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series, alternates between evocative word-sketches of images from several of the panels, snatches of conversation overheard in the gallery, and the speaker’s reflections on how (and whether) she can relate to the story of forced migration told by the paintings. Honoring the particular history of Black people in the South, she asks “What do I know about exile?” and “Am I allowed here?” The frustration she encounters in trying to make accurate sketches from the paintings becomes a metaphor for the limits of empathy in fully grasping the trauma of others:

I sketch her roughly

to scale.

Minus signs for knuckles:

those, I can handle.

My pencil struggles

To place the steep black rectangle. . .

The fifth “Dear Memphis,” poem is another acknowledgment of white privilege in the context of a reflection on the speaker’s relationship with Minnie.

Never folded

a single shirt, though I’d root

through the baskets to claim

my own—

bless my small body, that white child’s ease

that I cannot, not ever, give up…

Self-implication becomes shame in “Swatch Test” (“tick back and forth— // You can choose what you want to be ashamed of— / back and forth across the wish.”) and resounds again in “To Belong Less to the Aggressor,” the most powerful of several poems exploring the speaker’s ambivalence about being Jewish. She claims that inheritance with phrases of Hebrew and descriptions of observance but also finds herself wanting to conceal it in the face of Jewish aggression and occupation: “I spoke aquí, así, / took another tongue / to belong less to the aggressor.” “To Belong Less to the Aggressor” also includes two passages exploring the etymology of the word diaspora, one of them evoking violence (“Disperse, the order / before the recorder hits asphalt.”) The other (“Dia, apart, / sperein, to scatter, like ashes”) sounds an elegiac note that runs through the collection and also calls to mind the “scattering” of the epistolary poems throughout the collection in their own poetic or editorial diaspora. (Drawing more parallels, this reader can’t help wondering whether or not it’s a coincidence that eleven, the number of “Dear Memphis,” poems and the number of short stanzas in the chilling, impressionistic “Descent Fragments” is a significant number in Jewish mysticism.)

On one hand, Edelman’s speaker chafes against her family ties, writing in the fourth “Dear Memphis,” poem, “I wanted to live / where no one knew / who I belonged to. / I wanted to tell you myself” and “What she wants/taken care of / I want gone” in an account of going with her mother to deliver an ancestor’s portrait to be archived (“The Portrait”). On the other hand, she includes moving elegies to her grandparents and writes a love poem (“Stone Way North”) that doubles as an ode to tomatoes grown on her rooftop in imitation of her grandmother, who is also the subject of the moving final poem.

Space permitting, every one of the collection’s 43 poems—including a documentary erasure, a cento, a concrete poem, and meditation on Biblical texts in addition to free verse lyrics, ekphrastic and epistolary poems—deserves mention and attention to its technique, its sounds, its interweaving of themes, and its metaphors, many hinging on specific details of the geography, geology, and weather of Memphis. Having grown up in Memphis and also studied geology in college gives Edelman a rich palette of detail with which to sketch (an activity that the speaker of these poems also refers to). Dear Memphis is an impressive testament to the synchronicity between a poet’s concerns, the subject matter that constitutes her materials, and her ability to make such effective use of those materials to express the process of grappling with her concerns. Edelman treats weighty subjects and complex emotions with masterful nuance, using questions and the comments of others to fill in the dotted outlines and white spaces between the mostly short, often staggered lines of these spare, resonant, abstraction-free poems. Despite the weightiness of their concerns, these poems are never heavy-handed or moralistic, and Edelman’s speaker is humble and honest about her role in a world of damage, injustice and inequality.

::

Rachel Edelman is a Jewish poet raised in Memphis, Tennessee who writes into diasporic living. Her poems have appeared in Narrative, The Seventh Wave, The Threepenny Review, West Brach, and many other journals. They have received material support from the City of Seattle, Office of Arts & Culture, the Academy of American Poets, Mineral School, Crosstown Arts, and Tin House and finalist commendations from the Adrienne Rich Award, the Pink Poetry Prize, and the National Poetry Series. Edelman earned a BA in English and geology from Amherst College and an MFA in poetry from the University of Washington. She teaches Language Arts in the Seattle Public Schools, where embodiment and care root her personal, poetic, and pedagogical practice.

Rebekah Wolman is a former middle-school principal, learning specialist, and English teacher whose poems have appeared in a variety of print and on-line journals and anthologies. She is a 2021 winner of Cultural Daily’s Jack Grapes Poetry Prize, the 2022 winner of the Small Orange Emerging Woman Poet Honor, and a finalist for the 2023 Naugatuck River Review Narrative Poetry Award. Her 2025 chapbook, What the Hollow Held, is No. 6 in the A.V. Christie Series from Seven Kitchens Press. A transplant from New England, she lives in SF, CA, on unceded Ramaytush Ohlone land, where she lazily tends a native plant garden. Find her on Instagram @rgordonw56