Interviewed by Romana Iorga

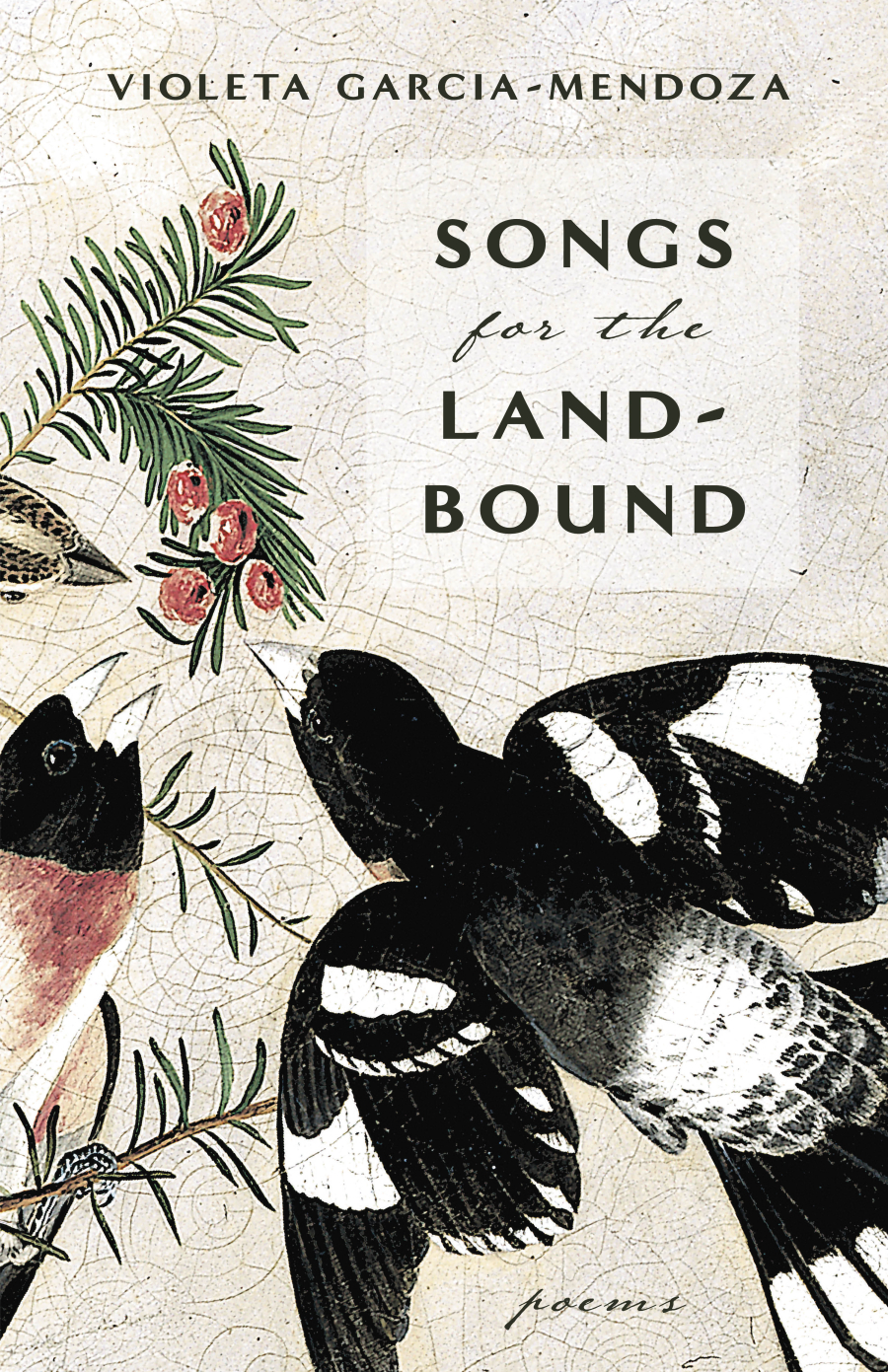

Romana Iorga: Dear Violeta, thank you so much for agreeing to this interview. I was moved and inspired by Songs for the Land-Bound and found it so rich and profoundly resonant to my own experience as a mother, poet, and human being living in this astonishing, heartbreaking world. Let me begin by asking you about the stunning cover illustration of your book. I’m blown-away by how accurately the Kidd/Audubon painting matches the thematic tapestry of your collection, including the proliferation of birds flying in and out of your poems. A quick search told me that the rose-breasted grosbeak from the painting symbolizes joy and hope, because of its particularly melodious songs and wide repertoire; renewal and growth, because it changes its plumage in winter; and finally, love and harmony, because it is a monogamous species and mates for life. Forgive my fascination with the grosbeak, but I have an inkling that you will understand it. I also adore the flying birds (they look like swallows!) drawn by your daughter in the table of contents and in-between the book’s sections. Don’t even start me on the swallow symbolism, especially that of a swallow in flight. There’s a lot of flight in these poems, addressed as they may be to those of us who are land-bound. How has the Kidd/Audubon painting revealed itself to you and what have its winged messengers imparted as you were putting this collection together?

Violeta Garcia-Mendoza: First of all, thank you so much for spending time with my book! Hearing how my poems connect with individual readers is such a bolstering thing for me as a poet, so thank you.

The birds in the physical manifestation of my book, from the cover to the section divider ornaments drawn by my older daughter, were one of those things that felt deeply right as soon as my publisher and I started brainstorming elements of the book’s design.

Birds and flight have fascinated me since I was a child, though I didn’t come to anything like birding until I was an adult. Like you mentioned, birds are varied, and beautiful, and musical, and symbolic. They’re also such an accessible manifestation of nature—whether or not you know their names or anything about them, you can find them everywhere (the more you look, the more you find, which is so rewarding; the more you observe them, the more your curiosity and affection grows). Birds are company, and mirror, and window in my life and in my poems, and I love how the Kidd/Audubon painting and my book cover’s grosbeaks hint at all of that.

RI: I’m drawn to the fluidity of time in your poems, its shapeshifting quality. In this collection, time is ubiquitous, permeating and permeable; it is also elusive. The present and the past often converge and that is a source of worry for the speaker. I’m thinking of the poem “Advanced Terrain,” specifically the lines, “Do you ever wonder if we keep / the past too close?” I tend to worry about hanging on to the past as well and sometimes wish for a touch of amnesia. In some of your poems, time is tragedy (“Fossil Record”), in others, it brims with possibility—like a trapped creature, it wants to be released “scattering light, past selves, seeds” (“Song of Past Selves”). Time may take on an ephemeral body, in which “the hours stretch like skin” (“Carrion Moon”), or it may easily shed it, leaving mere traces of itself in its passage: “the years like fingerprints / we’ve left upon each other’s bodies” (“Nocturne”). In the poem “Ongoing End of the Once World,” time has a voice, it can ask questions, it has tunnel-vision. It seems to me that the closer time is to being personified, the less omniscient it becomes. I prefer this kind of time to a know-it-all time; in other words, I prefer a flawed, anthropomorphized version of time to a flawless, godlike one. How aware are you of living in time, observing its passage, writing about it? And as simple as this question may sound, is time a poet’s ally? We, poets, certainly tend to imbue it with a lot of power.

VGM: Thank you for that close reading of time in my book! I have a complex and evolving relationship with time, like many of us, I imagine. Often in my daily life and in my poems, I feel time like air pressure around me—variable and characteristic of its own kinds of weather. Sometimes that weather lends itself to presence, and other times to ruminating about the past or worrying about the future.

What probably started my fixation with time was the first decade of my life with type 1 diabetes (so say from age 12 to 22). Although I did have an amazing pediatric endocrinologist at diagnosis, I also later had some medical professionals who casually put terror into me about what I shouldn’t expect as far as length and quality of life. From talking with other diabetics who were diagnosed around the same time I was, these kinds of scare tactics were not uncommon, and meant to be “motivating”; instead they created a terrible anxiety that shaped a lot of my life choices as a young adult. I pushed myself to triple major in college and graduate early, got married young, became a mom young, and tried to front-load as many personal milestones as I could because I had been told by enough medical professionals to not picture much after forty. Forty was the terrible specter after which who knew what I would be healthy enough to make or do or live. For a long time, I felt like I was living with a countdown clock. I couldn’t even stand to wear a watch.

And then… I turned forty, and to my surprise and amazement, was just as healthy and capable as I had been before! I hadn’t experienced any complications, my quality of life wasn’t diminished. Everything went on (as if, why wouldn’t it?), and that ceiling of dread lifted.

I don’t think I’ve come to terms with that shift fully yet, but time has become more associated with possibility and hopeful defiance for me since then. There are glimpses of that in a few of the poems in Songs for the Land-Bound, and I’m looking forward to seeing how that shift influences new poems too.

RI: My heart goes to your childhood and young-adult selves who felt so hounded down by time. And I’m so glad that time has acquired more positive connotations for you. I love the phrase “hopeful defiance” and see hope as a unifying thread in Songs for the Land-Bound. It is present at the very beginning of the collection in the poem “Heart, Darkness”: “[W]e live / as we dream—alone, capable of anything: / grief, wilderness, wildness, / hope.” Hope, nature, motherhood are intertwined in your work. The speaker in many of your poems yearns to be surrounded by things that grow to find solace, “to feel holy, whole” (“A Skeptic’s Guide to Birdwatching”). In the poem “Midwinter” she asks, “What wouldn’t a body try to counter hopelessness?” and goes on her daily walk up a mountain to become more anchored in herself. But all things that grow also diminish, and hope is one of them—it is seasonal, perishable, “ticking its decay like any isotope” (“Ongoing End of the Once World”). Thankfully, hopelessness is equally prone to decay. I love that your collection ends with the dreamlike “Goldspell” (such an amazing title!) and its final, memorable lines: “hopelessness / is a room I’ve had to bless & burn.” Tell me, what are your rituals for combing this “litter-rusted world / for hope” (“Decades Later, You Misremember Wildflowers”)? What centering practice has given you meaning and fulfillment?

VGM: Hopefulness, like belief, often feels like some mystery that ebbs and flows in me. But regardless of whether I am in a period where hope feels easy or difficult, I value the reach for it as life-sustaining, and what orients me towards hope centers deep attention, connection, and openness.

Sometimes that looks like walking my dogs, hiking, spending unhurried time in nature, birdwatching, reading, listening to music (and sometimes singing along badly), looking at art, playing the piano; often it looks like learning, daydreaming, praying, questioning; frequently, it looks like concrete acts of care and kindness, tangible reaching out within my family and beyond. All of these show up in my writing, so I should name that as a practice too.

RI: I’m so glad you said that, because I also see writing as a kind of hope and I noticed a similar sensibility in your work. In “Blank Canvas,” for instance, the speaker addresses what I assume is an alter ego, perhaps her writing self, saying, “More than once a poem has saved your life / & so some sense of life debt haunts you.” Tell me about this life debt, this “romance / with the unreliable,” where did it begin? Do you remember writing your first poem? What language(s) formed your first worldview, what books, what stories; how have words buoyed your younger selves toward the poet you are today?

VGM: I very much believe in the way words can offer company and solace, and stories and poems have absolutely buoyed me throughout different parts of my life. When I read something that moves me, I feel gratitude and loyalty towards the work, its world, and its author, and that’s something that has been true as long as I can remember.

I was an only child and spent a lot of time by myself while I was growing up. My mom raised me as a single parent, for many years in a country that was not her own, while working full-time in a demanding job; something beautiful that she did for me was surround me with books, with art, with open-ended toys that encouraged my imagination. It wasn’t a typical childhood in that I didn’t have siblings, or close cousins, or lots of other kids to play with, but I rarely felt lonely or bored because I had access to this chorus of stories and I always had somewhere to go in my mind.

My worldview was shaped by growing up in both English and Spanish simultaneously; I heard both, spoke both, and read in both from an early age, though which one I considered dominant depended on where we were living. My favorite childhood books in Spanish were the Antoñita la fantástica series by Borita Casas, Adiós, Josefina by José María Sánchez-Silva, and Cuatro o tres manzanas verdes by Carmen Vázquez-Vigo. In English, I loved Francis Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, and Johanna Spyri’s Heidi (though of course Heidi was originally written in German and subsequently translated). I also loved my Cuenta Cuentos, which were a collection of cassette tapes full of stories and songs for Spanish children based off of Marshall Cavendish’s UK Story Teller series. I literally wore them out from playing them so much! I cried when I found they were available on YouTube, though I haven’t yet let myself rabbit-hole into their nostalgia as much as I’d like.

The first thing I remember writing was a fable in Spanish about a mop who complained too much. I wrote it for a school contest in first grade, I think (though it failed to win even an honorable mention, to my great shock, haha!). I didn’t start to write poetry until I was around thirteen, when I became influenced by psalms and song lyrics in equal measure.

In the ensuing years I’ve written fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and I always say poetry is the genre I’d save in a fire. It’s musical and mysterious and portable in ways other genres can’t easily manage by nature of their longer forms and conventions.

As an adult reader, poetry has accompanied me, challenged me, comforted me, and inspired me more than fiction or nonfiction, so that’s the “life debt” I write about repaying in “Blank Canvas.” Poets like Maggie Smith, Catherine Pierce, Claire Wahmanholm, Chloe Martinez, Chelsea DesAutels, Carolyn Oliver, Emily Mohn-Slate (among many others) have helped me keep going in significant ways and moments with their work. I’d love it if any of my poems could do that for someone else.

RI: I’m fascinated by your growing up bilingual and being influenced by the texture of language and the literature coming from both English and Spanish. And speaking of that texture, I love the sound of compound words in your poems, how they roll off my tongue, what I imagine and feel when I utter them. I’m talking about words like sorrow-widening, silt-swaddled, sun-stunned and sun-gained, sleep-flown, splay-winged, litter-rusted and grief-tinged, bloom-drunk, shard-sharp, time-bent and flower-bowed, bruise-blues, wonder-drowned and I could go on and on. Just enumerating them is a poem in itself. How have these words come into being? I’m positively wonder-drowned. Also, tell me a bit about your writing process. Do you start with an image, a word, a voice? How long does it take for a poem to coalesce? When do you know that it has become its own thing, that it no longer depends on you?

VGM: For the first part of your question… I think a bit of my creative compound word choice is indeed a side effect of being bilingual and of feeling sometimes muddled and often tired when I’m writing! I love words and try really hard to use them properly, but the aforementioned circumstances do cause me to blend words to serve as an impressionistic sort of shorthand while freewriting. I usually note these phrases in my drafts so I know to rework them later, but sometimes they’re inventively useful and end up staying in the final version of the poem. Thanks for giving them some love!

As far as my writing process goes, usually my work starts with preoccupation and that attaches itself to imagery and sound. The sense of preoccupation may not even be something I can label until after the poem is far along, or even done, but I recognize it as a sort of insistent humming in the background. I feel like that’s what steers me towards the imagery I notice and the sounds I bend towards.

Almost everything starts with freewriting. Because I think at the speed of my typing (much faster than I can write longhand) and I had years of piano lessons (and practice) that built an association between an at-the-keyboard posture and a daydreamy in-my-own-little-world-ness, I find that typing without stopping or editing or self-judgment for 10 to 20 minutes is a really helpful way to access my internal thoughts and music. I keep a document of dated freewrite fragments like a journal, even though I don’t do them every day, and I regularly mine those for material. After freewriting, my process most resembles collage as I combine and recombine and connect these sort of scraps.

I am a slower writer than I’d like. Most of my poems take around a dozen drafts before they coalesce into something that makes enough sense to show anyone else. By then, my vision is clouded with all the previous versions, so it really helps to share the poem with a few writer friends to find out if it’s working, what has heat, what might be cut. Then I do another round of edits and let it sit for a little while.

It’s hard to say how I know when a poem can stand on its own. I think it’s when I can see it (almost) as if someone else wrote it, when it surprises and moves me without the scaffolding of those prior versions, and when I’ve run out of edits to strengthen it. I pay attention to the feeling in my body when I reread it in its latest iteration and try to tune into a sense of intuition.

RI: Your poems abound with tenderness for the world we live in, its questions, its confusions, its unknowns. I’m thinking in particular of the poignant “Anthropocene Aubade,” in which the speaker confesses to loving the world “like an amnesiac, lov[ing] / even its absences, its sorrow-widening light.” Another example is the enchanting “Parable of the Swallows,” where the birds’ “songless absence” in winter was explained by long-ago scientists through a series of fantastic scenarios, which I found endearingly imaginative and poetic. What might be the mysteries we misinterpret today, what enigmas are on their way to becoming the stuff of tomorrow’s poetry? And what perplexes you, what do you wish you knew more about? What do you like to read, watch, explore; what feeds your curiosity?

VGM: I think humans in general are often uncomfortable with mystery and prone to overestimating our knowledge/technology/progress as a society. We live in a time when we have so much information available at our fingertips and yet this clouds our perception, tempting us into believing too many things can be instantly or easily know-able. We confuse the cumulative practice of learning with an endpoint of knowledge.

As humans we probably deeply, fully, connectively, accurately know very little; at least I feel like I do. But that’s okay; if everything abounds with mystery, then we get to keep at our studies, our questions, our curiosity, our awe.

Personally, I wish I knew more about SO MUCH! I love the feeling of brain tingles that comes with learning and, with the right resources, I am truly delighted to learn more about anything, no matter how random it might seem. I love when someone tells me about something they are interested in; I love the contagiousness of other people’s excitement and fascination. (This is one of many reasons why I love children— they are reliably great at telling you about what they like and why— but I’ve learned recently that many podcasts do this well too, so I’m trying to work more of those into my days!) I’m using the word “love” a lot here, but it’s because curiosity, like love, influences and expands the world.

As far as what feeds my curiosity—reading, of course, nature, music, spending time with my teenagers (watching movies, shows, and sports with them, talking with them about books, sharing music recommendations, listening to them process the world), hiking with my husband, connecting with other writers, going to a museum… I’m certain I’m forgetting things since I’m someone who can keep herself entertained with a cardboard box. So much so that I took inspiration from an Amazon box for a line in “Anthropocene Aubade!”

RI: Speaking of love and curiosity expanding the world (my world!), I adored the lilting enumerations of herbs and wildflowers in “Nocturne” and “Decades Later, You Misremember Wildflowers,” the delicate presence of things about to disappear in “Naming Absence.” Your poems are so firmly rooted in the physical world. It’s hard to write about abstract concepts like absence or silence and make them appear concrete, yet I find myself transfixed when I encounter lines like these: “Silence scares me // unless I tell myself it doesn’t mean no response” (“Advent in the Hall of Architecture”). Even an imagined alternate life gathers flesh in “Ode to Fog”: “In another life, I might / have been the veil scraping against // the corners of a sooted city or the slice / of lamplight or the galloping black.” Is there a secret to making things that one cannot ordinarily see or touch visible, tangible? To paraphrase Blake, how do poets cleanse the doors of their perception and see everything as it is, infinite?

VGM: I would love to answer this question as thoughtfully as you’ve asked it, but I’m not sure if there is a secret to combining the concrete and abstract, that I manage it by intention. When drafting I collage, combine “high” and “low,” approach from different angles; I’m messy, I make a lot of attempts. I think that contributes to the effect. There’s a bit of “looking alongside” rather than “looking at” (as explored by C.S. Lewis in “Meditation in a Toolshed”), and a lot of respect for mystery, but it’s trial and error. I want a poem to hook me on different levels, both as a reader and a writer, and in my work those levels tend to be my everyday physical world and the abstractions I orbit with my memories and dreams and questions and worries.

RI: This is such a good segue into my next question. I was so affected by your poems about motherhood, children, hospital visits, family trips, the poems about the chaos, fragility, and messiness of daily life. In “Midlife,” you write some of my favorite lines: “I am trying to remember who I am if not a consonance / of clocks set to the needs of others. What does a woman do / with extra love if not keep mothering?” What stands out to me—perhaps because I feel so often overwhelmed by worry for my children and the world they have to live in—is your speaker’s constant fight against fear and despair. “The mother is a sharpened knife // with kitchen blues,” you write in “Still Life with Television II.” In another poem, the speaker describes motherhood as an “everyday sandbagging // of the home, the heart, the fragile bodies” (“Diagnostic Echocardiogram”). It must be an evolutionary advantage that mothers are capable of imagining the worst kind of scenarios and taking steps to stave them off; this ability may very well have saved many of our ancestors’ lives. But it’s a heavy burden when “the mind / endears itself to past and possible disasters” (“Insomnia”). Has writing about your fears helped you in any way to overcome them? Is a mother who is also a poet better equipped to process the gamut of emotions and experiences that comes with motherhood? Have your mother and poet identities been mutually influential?

VGM: It means so much to hear those poems spoke to you. Thank you for sharing that.

I was a deeply-feeling, emotional-processing, what-if-asking type of person before becoming a mother and motherhood has only underscored those qualities (in life as in my book’s dedication, I say that my children have turned the volume up on everything).

I wish I could tell you that writing about my fears had helped me overcome them, but alas, they persist. What writing has done has been to help me notice my fears and anxieties (and related overwhelm and frustration), put them into words, and sit with them with more understanding and compassion, rather than try to bully myself out of them. It’s not a cure for that shade of darkness, but it’s a decent coping mechanism.

I do think my mother and poet identities are mutually influential (and positively, so long as we’re not talking about how writing and motherhood compete for practical time). The vulnerability, tenderness, flexibility, persistence, and patience I’ve learned from motherhood has only helped me as a poet. The play, communication, creativity, and awe I’ve learned from poetry has only helped me as a mother. The identities vine and electrify around each other.

RI: What a beautiful image! In my mind I saw endless intertwining strands of DNA—a poet’s DNA. Last but not least, is there a question you wish I had asked you today, a moment of insight or wonderment that you would like to share with our readers?

VGM: The last thing I’d like to end with is something I put in my book’s acknowledgements, but it is an encouragement that bears repeating, especially in challenging times. “To the long current of past, present, and future poets, writers, artists, musicians, and other creative people everywhere: your attention, imagination, and humanity are a life raft for us all; please keep going.”

RI: Thank you so much for offering us a glimpse into your workshop, Violeta. Wishing you much joy, inspiration, and fulfillment in the new year!

VGM: These questions have been so thought-provoking, Romana. Thank you!

::

Violeta Garcia-Mendoza is a Spanish-American poet, teacher, and photographer. She is the author of SONGS FOR THE LAND-BOUND (June Road Press, 2024), and her poetry has appeared widely and been nominated multiple times for both the Pushcart Prize and Best of the Net. Violeta lives with her family in western Pennsylvania, where she is part of the Madwomen in the Attic Writing Workshops at Carlow University.

Romana Iorga is the author of Temporary Skin (Glass Lyre Press, 2024) and a woman made entirely of air (Dancing Girl Press, 2025). Her poems have appeared in various journals, including New England Review, Lake Effect, The Nation, as well as on her poetry blog at clayandbranches.com.

ID: Cover of Songs for the Land-Bound by Violeta Garcia-Mendoza.