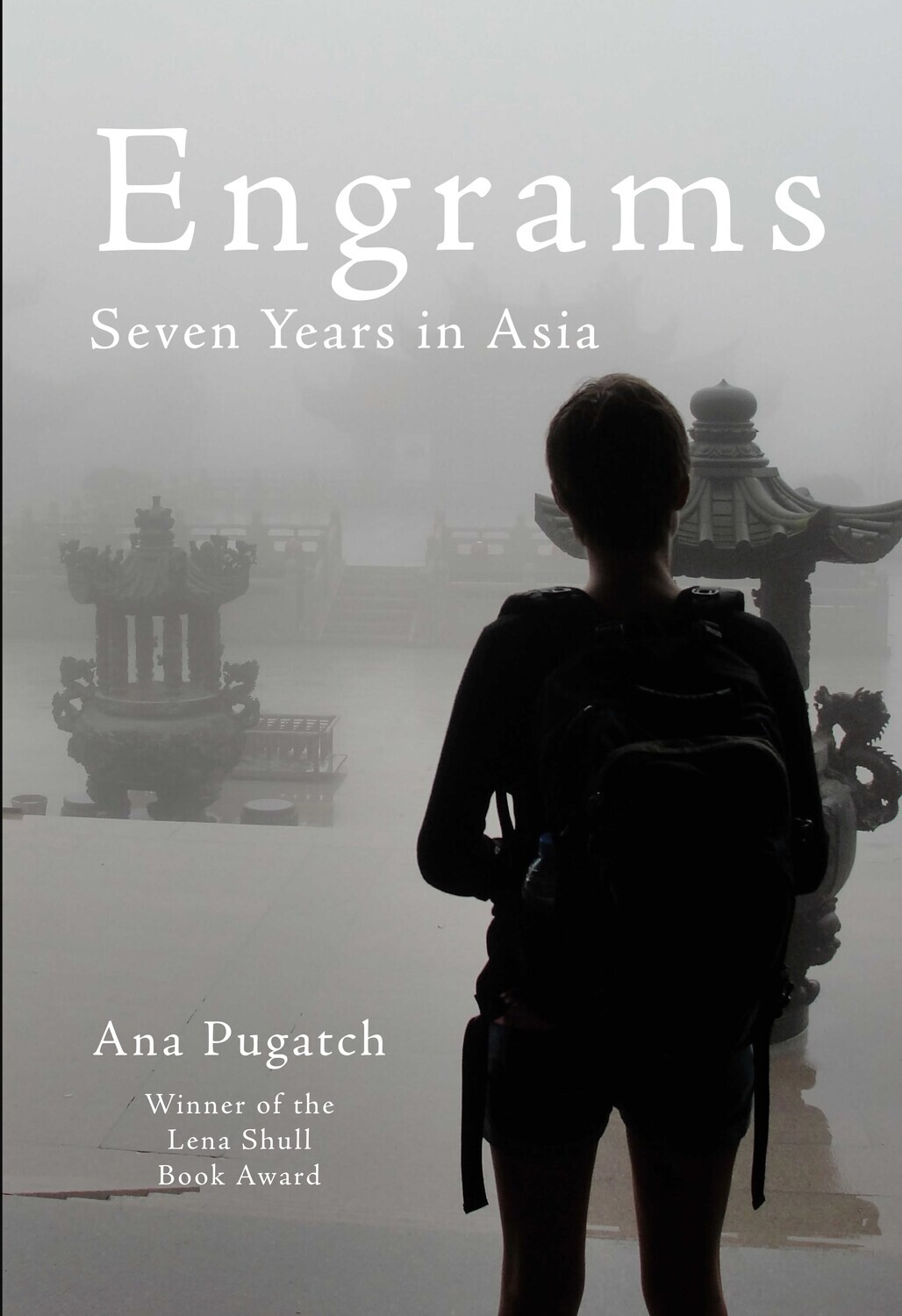

Engrams: Seven Years in Asia, by Ana Pugatch

Redhawk Publications, 2023

Review by Stephen A. Allen

::

Engrams are curious artifacts of early 20th century research on the brain. The term—coined by German researcher Richard Semon (1859-1918)—refers to a physical imprint on a cellular level of a memory, a sort of permanent record of a set of stimuli that can be recalled when conditions are right. In Ana Pugatch’s hands, engrams reveal themselves in a series of snapshots of her life in China, Thailand, and back home in North Carolina. These snapshot memories are replete with observations of the natural world and the world that humans have built in it—from apartment complexes to working monastic retreats—frequently zooming in to provide a depth of focus on the most minute details: the sharpness of a rice plant, the thready legs of a walking stick, the movements of a praying mantis.

About halfway through Engrams, at the end of the first of the two sections set in Thailand, Pugatch provides some insight into her creative worldview. The poem, “Ars Poetica,” begins with the poet thinking she has seen a hummingbird moth alight in a bush, only to discover instead an injured bat. Not a desired outcome: “I hate bats.”

I am always followed by bats,

both in and out of sleep. Caged,

wooden slats—it is my job

to lift the latch . . .

A bat launches out of the dreamed cage and into her face, getting hit for its trouble until it is no longer a threat. But these bats are not merely physical flying animals:

I wake to its musty smell which

follows me to the light, to the desk.

When I write I feel the brush

of its hopeful paper wings.

Unrequited repulsion: the bats want to be near the poet, want to be made manifest in the written word, even though the poet may find this “harrowing.” This ambivalence may be the result of the poet’s position as something of an intruder: a lǎowài, a foreigner, someone literally “old” and “from outside” (as the first poem of the second China section defines it). As many of the poems in Engrams show, the parts of the world Pugatch found herself in made her feel foreign indeed, but she is drawn to them anyways. She has forced herself to lift the latch on the cage, and the result is a book of deep observation, a tracing of the physical imprints of memory onto paper.

Pugatch initially went to China to teach English, and the first section of Engrams indicates that this was not an entirely pleasant experience:

No point returning home

when home has no heat. Everywhere

is the outskirts of campus, of town,

of the province—unlit. (“Teacher’s Nocturne”)

Even a visit from the poet’s mother is fraught: “The woman sensed that I now / looked down on her” (“My Mother’s Visit”). Still, Pugatch’s students provide some relief. They teach her “how / to ride side-saddle on the back of a bike,” conserve paper to her bemusement (“each piece / was creased and carefully torn even when I asked them / to use fresh ones and not roll them into scrolls”), and give her “boxes and boxes / of mooncakes stacked up on my desk.” Unfortunately, Pugatch tastes one mooncake and discovers that they are not for her, so she leaves them outside the door to her apartment at night, and in the morning “when I left I didn’t notice that the boxes / with their silver bows / were gone” (“Mid-Autumn Festival”). Even the closeness provided by the students seems somehow illusionary, disappearing unnoticed overnight.

A sense of alienation becomes more acute in the second China section (the third section overall in the book). Even a visit to a five-star compound for transplanted foreigners ends in disappointment: “I consider wading out to touch its bark, then notice the twin lines of electric wire running the length of each wall. Here luxury bulldozes the edges of the real” (“Zhuhai’s Vacancies”). A trip to the Great Wall results in miscommunication (“But my tones are off; no one / can understand me”) and a moment when:

One man reaches

out to touch my hair. When

I remain still, a dozen hands

do the same. It’s a holiday. (“The Great Wall”)

There are other crises: a burst water pipe and the death of a fellow teacher, suggestions of a failed romance, a pilgrimage complicated by a flood:

When the river washed away the dirt from the hills—when the one road became a river

and the river ran brick red—the monastery began to ration its food. The monks didn’t

mind, but reining in the appetites of lǎowài is no easy task. (“The Monks Took Pictures”)

There is a sense in these two sections that Pugatch is a stranger, not so much in a strange land, but in a place that she had hoped would be a home. Instead, she finds herself misunderstood, even an object of amusement, in a landscape of concrete residences and empty temples. The snapshots of memory are more like the photos of a tourist than the portraits of a native.

Unlike most of the sections set in China, the sections set in Thailand are teeming with animal life. The first poem of the second part of the book begins with birds: “The white egrets in the tree / tuck up their legs, settling into / the noon heat” (“Lumphini Park”). From there, it’s on to monitor lizards, house geckos, and a desiccated seahorse that brings a bad night:

Dead dreams of an estuary.

I prop him up in the bathroom for a day.

After a fit of nightmares I return

to the shore, bury him quietly in the dark. (“Estuary”)

Despite being long dead and dried out, the seahorse demands some honor be paid to the fact that it was once alive. Even the language seems more of a living thing:

But I can do this trick with Thai: not catch

the words I’d hold on to otherwise.

I return from the nothing-cave, language flits

and settles—always light-winged, iridescent. (“Calcite Cave”)

The Chinese language sets Pugatch up for misunderstanding, but Thai flits. In the two China sections, words come from toadstool-shaped speakers, are carved in stone, and are uttered badly by a fevered foreigner. In Thailand, the language is a delicate creature, a living insect flying about.

As in China, Pugatch gets caught in flooding in Thailand, but even here the onset of the flood is signaled by :

At first thunder the cockroach retreats

behind a loose tile, its appendages still.

The deluge dissolves the blue turrets

of the mosque. A fourth call to prayer—

rain or shine, rain or shine. (“Bangkok’s Rainy Season”)

A flooded street, instead of being filled with silt, carries “a bobbing tire, / a Pringles can, and umbrella // with twisted spines,” At the school where Pugatch teaches, the children waiting for her suggest she swim in, delighting her that, “They remember swim!” (“Tail-End of the Typhoon”). In the two China sections, life seems mainly to exist largely at a slight remove from the natural world, or at least embedded in a constructed environment. In the two Thai sections, human and animal life mix in a glorious riot. The result is a variation on sonata structure, the alternating sections playing off each other, which gives Engrams a dynamic back-and-forth movement.

The return to North Carolina in the fifth and final section of the book is marked first by the loss of a collection of souvenirs:

Airline’s message:

“Sorry, it’s gone.”

Farewell wreckage—

rose-fingered dawn! (“Lost Luggage”)

A happy accident perhaps, as the loss of the past allows Pugatch room to consider the present. Her Laotian in-laws offer an additional fresh start, visiting “the new house first / to ritually cleanse and spend the night” (“House Blessing”). The book ends with Pugatch envisioning her infant son in his carrier, in the snow, facing “a single dogwood” in a field where the poet had previously spread someone’s ashes. She wants to hold him,

But I cannot pick him up just yet.

He sleeps, he sleeps

on the wind and I remember now—

the ashes scattered here

were mine. (“The Clearing”)

The ashes are from “a time before”; the child is in the now and provides a link to the future. The engrams from seven years in Asia give way to the potential of new memories. Although this final section is brief, it provides a sort of resolution to the dialectic underlying the rest of the book. Out of the alienation of China and the liveliness of Thailand, Pugatch has arrived at a new place, surely to be explored, but perhaps from a distance: the eyes of the child in his carrier are still closed, but when they open, what will they see? What engrams are waiting to be imprinted? There is an interesting way forward here, which leaves the reader wanting more and looking forward to a second book.

::

Ana Pugatch was the Poetry Heritage Fellow at George Mason University. Her work has been featured in Literary Shanghai and The Los Angeles Review, among other places. She now lives in Raleigh, NC with her husband and two children, and serves as a committee chair for the North Carolina Poetry Society.

Stephen A. Allen was born in Vermont and currently lives in Michigan. He has an MA in Creative Writing from the University of Illinois at Chicago and also studied poetry at Amherst College and the University of Notre Dame. His poetry has appeared most recently in Northern New England Review, MacQueen’s Quinterly, and Rattle.

ID: Cover of Engrams: Seven Years in Asia by Ana Pugatch.