Interviewed by Millie Tullis

Millie Tullis: To start, thank you so much for being willing to answer a few questions about your new book, The Alcestis Machine! One of the things that I find so remarkable about your work– thinking not only about this book, but maybe especially this book– is the role of imagination. In Inside the Storm I Want To Touch the Tremble, your first full-length, and in Mirror Factory, one of your chapbooks, you pull speakers from all over history, myths, time and space. The Alcestis Machine seems like the natural progression to me as your reader– your imagination is totally unleashed in these poems that collide space and history, the intimate and the surreal.

For example, many poems begin almost as an exercise in imagination, “In another life, I am…” One of my favorites of these is “In another life, I am a voice for hire” at the start of “Deep Learning.” Although imagination is obviously key to the making of art, it can be hard to talk about. I’m thinking about Mary Ruefle: “It is impossible for me to write about the imagination; it is like asking a fish to describe the sea.” But, is imagination something you think about deliberately as a writer, something you exercise or stretch? And/or, how has your imagination changed/developed through your poetry practice?

Carolyn Oliver: Thank you for this thoughtful question, Millie, and thank you for the chance to talk about poems with you!

Sometimes, writing imaginatively feels transgressive to me, perhaps because it’s such a pleasure. Writing about the here-and-now is, for me, much more difficult. Directness is not my strong suit, I’m sorry to say. To slip into another persona for a few hours, to research pigments or frog-songs or etymology, to extrapolate from a miniscule detail in a painting or book, to preserve, a little while longer, an archival object in language—these are delights.

My mind works like a “what-if” generating machine, so often I find myself bubbling over, like Strega Nona’s pasta pot, with recalled details and odd scraps of language and photos of strange signs—and no sense of where to begin, how to corral these materials (and the materiality, is, I think, important to me)—most of which have associated flashes of feeling that resist being languaged—into poems.

(My mind also works in run-on, digressive sentences.)

“Deep Learning” is the result of imagination primed by circumstance. The inciting incident for its composition was an Amber Alert phone call about a missing baby girl with a butterfly on her shirt (she was found, safe, very soon afterward; otherwise, I don’t think this poem could exist). The call came in woman’s voice, but the syllables were generated by a computer, the emphasis just a shade off. At the time—this was just a couple months before Chat-GPT was released to the public—I’d been reading a (nightmare fuel) book on LLMs and AI; had just seen a demonstration of an AI voice-model generating new “speech” after “hearing” a few minutes of a reporter’s voice; and had recently heard a recording of the sound of thousands of migrating monarchs waking up in a forest. All of those circumstances inform the poem, and probably the impulse to imagine what it would be like, to be a voice actor hearing one’s own voice on a robocall.

MT: Thank you for that reply—I love picturing your mind working like Strega Nona’s pasta-pot in the hands of Big Anthony, like a big “what if” machine.

I am amazed, always, by your range of form and inventive forms. In The Alcestis Machine, you have poems like “Winter” and “Poppies” that use four lines from another poet (Edna St. Vince Millay and Sylvia Townsend Warner) as your own stanza’s end lines. Visual poems like “Walking Alone” and “Night Flight” begin and end with short, one-word lines but stretch to a long line in the center of the poem, like a horizontal stalactite on the page. You have poems that read like scripts or conversations, micro-poems and prose poems. What forms have been most generative for you? Do you invent new forms often, or have favorite restrictions you return to again and again?

CO: Thank you for noticing those poems! “Winter” and “Poppies” are glosas, a form I first learned from reading Canadian poet P. K. Page. They’re quite tricky, in part because it’s difficult to find four consecutive lines in an already-existing poem that (a) can serve as standalone stanza-ending lines in the new poem, (b) will also work in terms of rhyme and syntax, (c) are lines I want to puzzle over for hours and hours.

“Walking Alone” and “Night Flight” are what I call doubleback fibs (there are a couple in my first book, too). I did not invent fibs, poems in which the syllable count of each line follows the Fibonacci sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, etc.), but my version extends to 13 syllables, and then the lines reverse the sequence, starting with a new 13-syllable line. It’s entirely possible, maybe even likely, that others have written similar fibs—I just haven’t encountered them yet.

I experience working with received forms as a kind of play—perhaps because I assign them to myself, from time to time, as exercises. I don’t think I would enjoy form very much if it had been required beyond the fifth and sixth grade. I could be wrong, though; I never took creative writing classes in college or graduate school.

When I experiment with form, I find that restrictions based on syllable count or end-rhymes or refrains become puzzles, and it’s effortfully rewarding to work on solving them. If I can combine two forms—for example, “In the Distance” is both a ghazal and an abecedarian—that’s twice the fun. There are plenty of forms, though, that I find challenging to the point of hopeless frustration—I’ve never written a satisfactory villanelle or pantoum. So much pressure on the repeating lines! I’m in awe of poets like Natasha Trethewey and Marilyn Hacker, who make the villanelle read so seamlessly.

MT: Thematically, this book is full of coldness– coldness in space, snow, frost, and ice. But so many of these poems are also about intimacy. You are frequently bringing images, language, and worlds together in wonderfully strange and surprising ways. In “Frost Heaves,” you pull Earth and Mars in close connection as you describe a rover. The rover moves across Mars, where “Ice bubbles… just as it ripples / New England roads… So the stranger and the landscape converge. Their surfaces break into each other.” In “Mast Year,” nature, intimacy, and loss are woven together tightly: “This is love, isn’t it? Leaving holes in our stories / as moths make lace from their hunger.” Was intimacy something you set out to write about in these poems, or something you found kept bubbling up as you brought images together until “their surfaces break into each other”? I’m also thinking about the intimate “you” in many of these poems.

CO: You know, I didn’t realize how much cold is in the book until you pointed it out—thank you for the insight!

I suspect the coldness and the intimacy—or convergence—you describe are twin products of circumstance: I wrote most of the poems in The Alcestis Machine during the first couple years of the pandemic. While my family was very fortunate to be safe and healthy, we did experience the unsettling combination of simultaneous isolation and lack of solitude that so many others felt. My guess is that the isolation is coming across in those cold images, and the need for solitude led to those convergences, in the poems addressed to the unnamed “you.”

This might seem paradoxical. I didn’t set out to write about intimacy, exactly, but I was so embedded in the hereness and nowness of my own life that I needed an escape hatch in the writing. Starting a draft with “In another life” and addressed to “you” functioned almost like a formal constraint, as if the poem were a puzzle to solve. A trick to let my mind unspool, into the pleasure of writing other worlds, other times, other lives. I still have trouble pinning down the identity of the speaker in those poems. The “you” shimmers in and out of view—sometimes an unreachable interlocutor, sometimes an amalgamation of impossible beloveds.

And I should probably say a word about “The Alcestis Machine,” the long poem that gives the book its title: in this poem, there’s a different approach to the speaker and “you,” informed by loss, and the specter of losses to come.

MT: If you were to place this book on a syllabus for a poetry class, what books would you feature alongside it? I’m not accusing you of designing a poetry course around your own book, of course (though it could be a pretty cool syllabus), but I’m curious what books you see in conversation with The Alcestis Machine– sister-books, cousin-books, foil-books, or other kinds of relationships.

CO: This is such a generous question, and every time I’ve tried to answer, I feel like an impostor, putting my work alongside the work of writers I admire so much. Herewith, a list of books (including prose, couldn’t stop myself) which overlap, in theme or subject or mood, with some aspect of The Alcestis Machine.

Burn the Field, by Amy Beeder

A Face to Meet the Faces: An Anthology of Contemporary Persona Poetry, edited by Stacey Lynn Brown and Oliver de la Paz

Men in the Off Hours, by Anne Carson

The Blazing World, by Margaret Cavendish

Stories of Your Life and Others, Ted Chiang

Fifth Business, by Robertson Davies

This is How You Lose the Time War, Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

Beyond Earth’s Age: The Poetry of Space Flight, edited by Julie Swarstad Johnson and Christopher Cokinos

Bestiary, by Donika Kelly

Wonder Tissue, by Hannah Larrabee

The Naomi Letters, by Rachel Mennies

Hologram, by P. K. Page

Scriptorium, by Melissa Range

Life on Mars, Tracy K. Smith

The Corner that Held Them, Sylvia Townsend Warner

poems by Thomas Wyatt

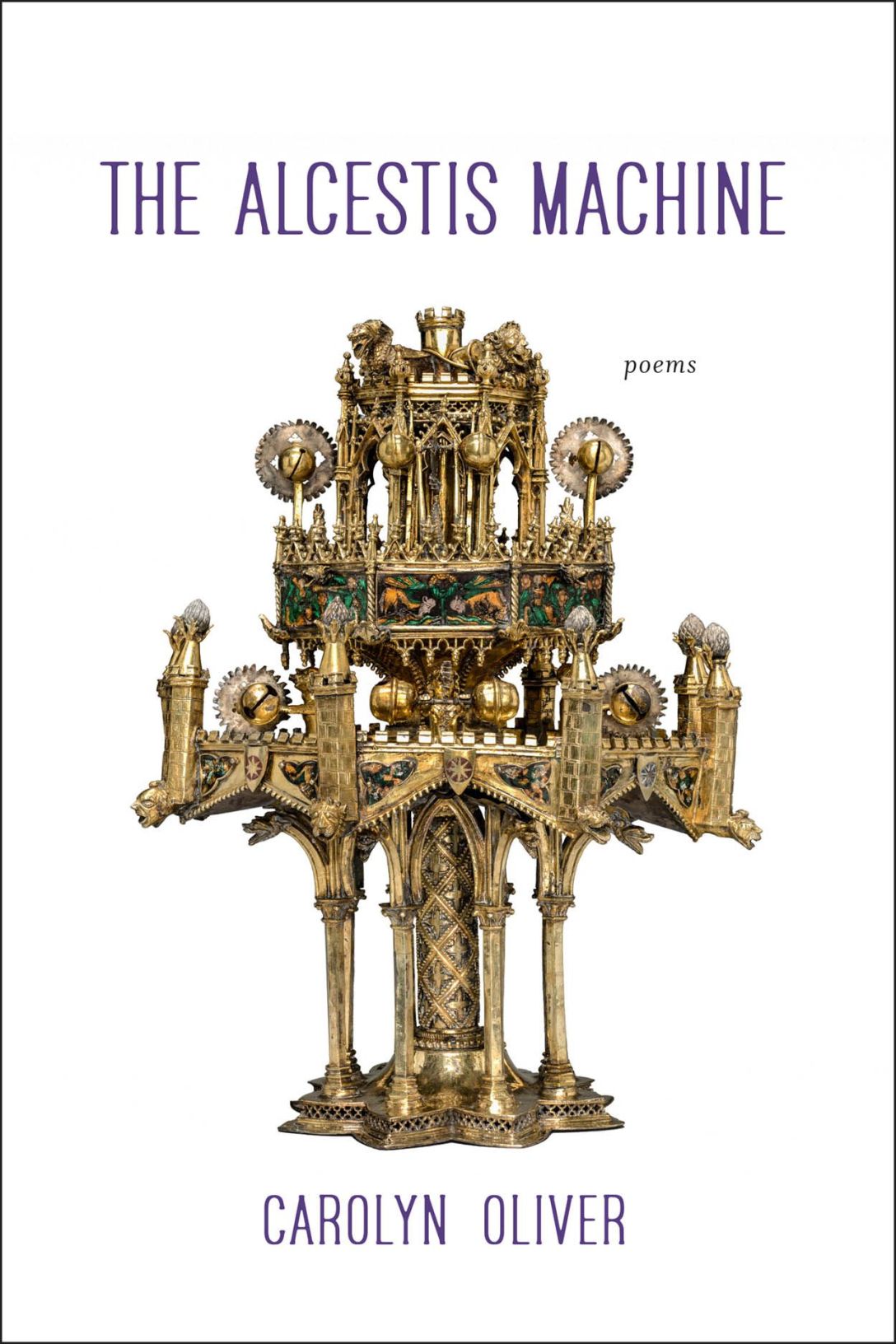

MT: Are there other texts (movies, music, pieces of visual art, performances) that felt foundational to your process as you were working on these poems? I’m thinking in particular about the relationship between the fountain you used as your cover art (a French table fountain from the 1300s) and a “De Profundis.” In this remarkable poem, the speaker (“a vampire biographer”) addresses “the Earth’s last painter…old enough to render / from memory pelicans and foxes, strawberries, / Hybrid daylilies I never saw I open” after the earth’s environment has been seemingly destroyed. The speaker recalls another artist from 1348 Paris, as she built a miniature fountain “beautiful and useless.” The speaker asks, “This machine, work of her hands, / would it stir you? Would you bend to drink / from the beaten silver basin, starlight on snow?”

CO: Thank you for giving me a chance to talk about the cover art!

Though I now live in Massachusetts, my home art museum is the Cleveland Museum of Art (free to all the people forever; everyone should go, their holdings are excellent). I’m very, very grateful that the CMA makes so much of its collection available for download and use. (The cover of my first book, Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble, is also based on a CMA-held work—Orpheus, a pastel by Odilon Redon.)

On a visit some years ago, my dad and I passed this object—and then I did a cartoon-style double-take and circled back because I just couldn’t imagine what it was. Weird shape, weird size, not for serving food, not a monstrance, etc. And it turns out that I’d never seen one before because these table fountains are very fragile and therefore quite rare. I took a picture, and started thinking about how to get it into a poem . . . but it took a while for the vampire to show up.

So yes, that object, in particular, was crucial to the writing of the book. Other crucial objects and texts:

The Lincoln copy of Magna Carta, which I saw (also with my dad) at Boston’s MFA in 2014; it and its dosimeter eventually made their way into “Lux Hours.”

Glass flowers by the Blaschkas at the Harvard Museum of Natural History

Illuminated manuscripts (various museums)

Blue: The History of a Color by Michel Pastoureau

The End of Everything (Astrophysically Speaking), by Katie Mack

Euripides, Alcestis, trans. Anne Carson

D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths

A range of texts from Tudor and Jacobean England, which I used to study: Shakespeare, Donne, midwifery texts, “wonder” pamphlets.

NOVA (many episodes)

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986; dir. Leonard Nimoy)

Metropolis (1927; dir. Fritz Lang) via the 1984 Giorgio Morodor re-release

The Big Sleep (1946; dir. Howard Hawks)

Janelle Monae, Dirty Computer

Leonard Cohen, mostly the later albums

Ralph Vaughan Williams, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis

Thank you again for your close and kind reading of The Alcestis Machine, Millie!

MT: Thank you for your poems and these rich and generous responses—it is always a pleasure to spend time with your words.

::

Carolyn Oliver is the author of The Alcestis Machine (Acre, 2024); Inside the Storm I Want to Touch the Tremble (University of Utah Press, 2022), selected by Matthew Olzmann for the Agha Shahid Ali Prize in Poetry; and three chapbooks, including, most recently, Night Ocean (Seven Kitchens Press, 2023), which was selected for the Rane Arroyo Series. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in Poetry Daily, TriQuarterly, Copper Nickel, Image, Consequence, and elsewhere. Born in Buffalo and raised in Ohio, she now lives with her family in Massachusetts.

Millie Tullis (she/they) is a writer, teacher, folklorist, and researcher. She holds an MFA from George Mason University and an MA in American Studies & Folklore from Utah State University. Her work has been published in Sugar House Review, Rock & Sling, Cimarron Review, Ninth Letter, SWWIM, and elsewhere. Raised in northern Utah, she lives in upstate South Carolina. You can find more of her work on her website.

ID: Cover of The Alcestis Machine by Carolyn Oliver.