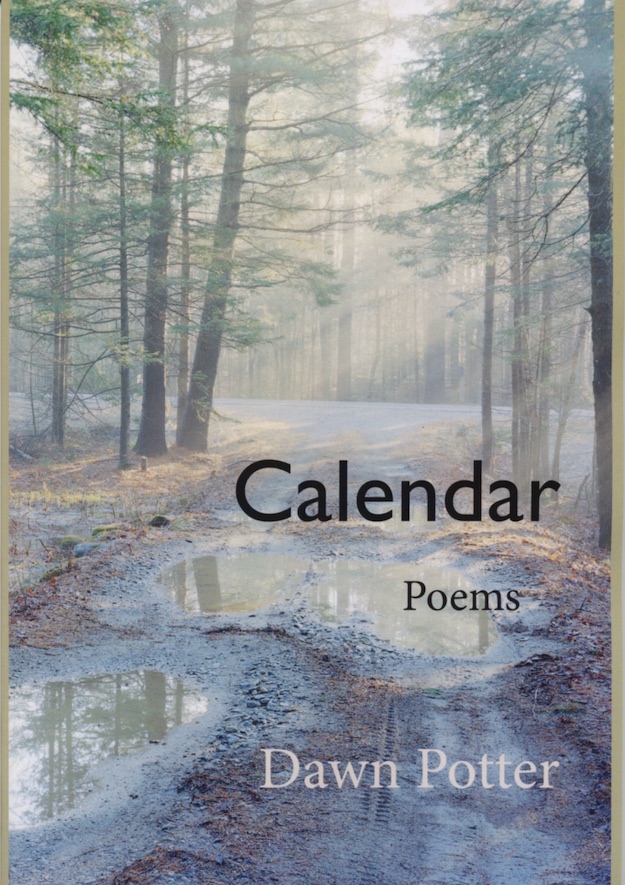

Calendar by Dawn Potter

Deerbrook Editions, 2024

Review by Rebekah Wolman

::

“the day passes, each hour a veil”… Quietly, that line from “Winter Fragments,” Calendar’s final poem, captures the book’s simultaneous preoccupation with the mundane and the mysterious.

On the most literal level, Calendar fulfills the promise of its title, organized by month in sections of two to four poems that frequently allude to their respective months or at least to the passage of time. From “A Month in Summer” (a nine-page poem inspired by the late 19th-century diaries of a Maine farmwoman) and “A History of Wash Day” (with the final line “No time to pray. Tomorrow is ironing day”) to “One Day” and “Play Clothes,” these are poems of daily domesticity and seasonal rhythms. But the familiarity of everyday life is balanced by its unknowability. The anecdotal “Polka Party” concludes, “… every time I squeeze / that accordion, it refuses to say a thing.” “Histoire” introduces six couplets of autobiographical vignette with the lines “The usual thing: / Time stood still for years, then fell off the table” “Fledgling” is a memoir in three tercets that infuses childhood’s “small delights” with “Ghosts shimmer[ing] on the broken doorstep, / rising though dust to become my own new skin.” These poems meditate on how time is spent and how it passes, but also on what it conceals (“What is it like to remember myself as absence? / Erasable. Erased.” from “Desk Work”) and what it leaves behind, as in the final two lines of “Night Driving on the New Jersey Turnpike”: “exits dazzle and vanish, dazzle and vanish, / a spool of missed chances, instantly forgotten.”

If the book’s true relationship to its title ends up seeming more philosophical than literal, its epigraph offers another framework for categorizing 40 poems that are deliciously varied in tone, form and content. In quoting Edmund Spenser’s introduction to his 1579 Shepheardes Calender, Potter presages the moody, sometimes aching, sometimes giddy, spirit of her own collection:

These… Aeclogues… may well be divided into three formes or ranckes. For eyther

they be Plaintive;… or recreative, such as al those be, which conceive matter of love, or

commendation of special personages; or Moral…. And to this division may every

thing herein be reasonably applyed: A few onely except, whose speciall purpose and

meaning I am not privie to.

Indeed, the voice in these poems is often plaintive, even desperate. “Help me figure out how to be human. / Help me,” pleads the speaker in “Things I Don’t Want to Talk About,” and the speaker in “My house is a badger’s tunnel” inhabits “… a cavern of echoes… as vast as despair, as shiny as coins.”

From the whimsical and wry to the sardonic, humor leavens the melancholy in plenty of what Spenser might call “recreative” lines and poems. The hilarious “moon poem” likens the moon to “that roommate who always / pays the rent late but not late enough to get kicked out.” “I want” is as romantic a prose poem as a person in love could ask for (“… I want to be… that big clumsy happy woman at the party… dancing her pigeon-wing shuffle alone in the corner and I want you to be there and I want you to be glad I came.”)

Potter is her most “Moral” in poems like “My soule a world is by Contraccion” (“Ten thousand people die in a moment, / and I am untying my shoes”) and “Enchanted Forest,” which gives voice to all that is endangered and vulnerable, linking humanity and nature in interdependence:

We were like you once, but now we are alders and sumac,

we are tiny pines choking the under-light…

When you tear off a little branch darkened with blood

I will cry out.

And then you will cry out also.

In keeping with the ambivalence that wracks the speakers of so many of these poems, they also challenge the boundaries between Spenser’s categories. There is humor in the most plaintive poems and morality and complaint in the most recreative. And in trying to make sense of poems whose images and associations are more bewildering, the reader can fall back—as Potter may even have done, marveling at the work of her own imagination and unconscious—on Spenser’s reference to the “few. . .whose special purpose and meaning I am not privie to.”

Calendar, complaint, recreation, moral discourse… To this reader, Calendar is all these but above all a poignantly ambivalent ars poetica. Through the voices of multiple poet-personae—the anonymous poet whom Odysseus charged with protecting Clytemnestra in his long absence; the 19th-century farm woman composing haunted verses mid-chore; Wealhtheow, the wife of Hrothgar from Beowulf, listening in the night for story and verse; and more than one speaker who may be the poet herself—these poems swing between pained resistance to and inevitable acceptance, if not embrace, of the poetic impulse.

In “What I Don’t Want to Talk About,” (while going on about all of it, with Potter’s characteristic irony) the speaker considers whether she “will change careers, find a job that isn’t so chockful / of words and tears… ” But the “words and tears” are ultimately irresistible to speakers such as those of “moon poem” (“… i am tired of writing moon / poems; this is the third one this week. the problem is / that the moon is so interesting… “) and “self” (“what battered bird / would choose any fate other than bird?”).

Despite the plaintive cry, “How will I be this world?” that ends “Desk Work,” Potter’s speakers cannot help but remain so porous to the world that poet becomes world becomes poetry.

in the land of poems everything

talks to everything else, and writing poems

seems to be the only thing my brain wants

to accomplish tonight. (“One Day”)

Readers should be grateful that so far, six poetry collections in, Dawn Potter has not decided to “change careers” and—to the extent that her own voice speaks through these poems—that she experiences “… the stodgy solid / glee of making a thing I want which is not patience but / greed.” (“Ode to Four Words I plucked at Random from a Book of Poems”)

::

Dawn Potter is the author or editor of ten books of prose and poetry–most recently, the poetry collection Calendar. She was a finalist for the National Poetry Series, and her memoir, Tracing Paradise: Two Years in Harmony with John Milton, won a Maine Literary Award in Nonfiction. Dawn has received grants and fellowships from the Elizabeth George Foundation, the Writer’s Center, and the Maine Arts Commission. Her poems and essays have appeared in the Beloit Poetry Journal, the Sewanee Review, the Threepenny Review, the Times Literary Supplement, and many other journals.

A former middle-school principal, learning specialist, and English teacher, Rebekah Wolman is a 2021 winner of Cultural Daily’s Jack Grapes Poetry Prize and the 2022 winner of the Small Orange Emerging Woman Poet Honor. Her chapbook, What the Hollow Held, is forthcoming in the A.V. Christie Series from Seven Kitchens Press. A transplant from New England, she lives in SF, CA, on unceded Ramaytush Ohlone land, where she lazily tends a native plant garden. Find her on Instagram @rgordonw56.

::

ID: Cover of Calendar by Dawn Potter.

I am so grateful to Rebekah and to Psaltery & Lyre for this thoughtful and generous review. Thank you all, and the best of holidays to everyone–

Such a rich and rightly deserved explication of the sweep and depth of Dawn Potter’s voice in Calendar. I so look forward to reading Dawn’s newest work.