Oracle Smoke Machine by Christianne Goodwin, with prints by Stephen Proski

Staircase Books, 2023

Review by Annaka Saari

::

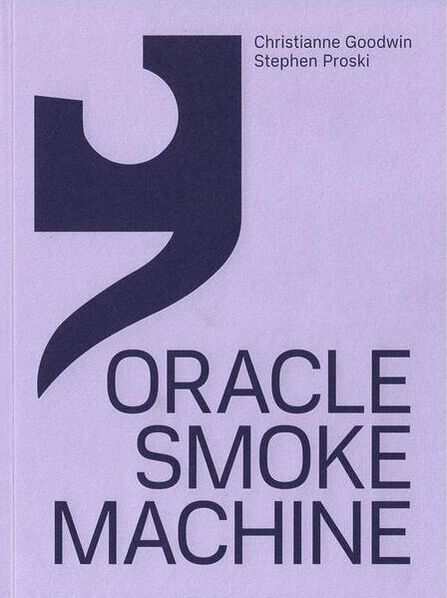

The second collection of poetry published by the Cambridge, Massachusetts-based Staircase Books, Christianne Goodwin and Stephen Proski’s Oracle Smoke Machine is a beautiful object: a paperback, the book’s cover is lilac, bearing plum-colored print and a symbol that suggests both speech bubble and curl of smoke, as well as a small staircase emblem on its spine. The collection is slim, composed of sixteen poems and sixteen prints. Still, in its short length, Oracle Smoke Machine twists and weaves through a diverse set of scenes, some anchored in the normal and others completely dreamlike.

We don’t have to look far into the book to confront the interplay between the everyday and the otherworldly. In the first poem, “One Night Only!” readers encounter “The Museman,” a host that can command the attention of an audience in Moscow, guiding them through “a pre-told visit from / the Devil himself,” a figure who exits quietly and makes off with the crowd’s umbrellas. On the page opposite the poem, a print by Proski shows a horned, dark creature framed by scalloped curtains and haloed by light, a swarm of green umbrellas surrounding him. In “Sunrise,” a later poem, we are brought back into the fold of reality, tracing the movements of an early-rising speaker leaving their partner in bed to walk along the seashore. “I went to see sunrise expand / over the stone-cut shore / and to get first pick of the sea glass,” says the protagonist, later assuring their partner, “when you wake, I will be in the kitchen / the sun and coffee will be warm.” In the poem’s final stanza, they state: “But you must look at my sea glass / and tell me that it is extraordinary / How else will I know it was all worth it?” Next to the poem, another print shows the little gems that the poem’s speaker had wanted so badly to be assured were “extraordinary”: irregular blooms of tan, cobalt, violet, light green, and frosty white laid over each other and sitting flat on the burnt-orange clay of the seafloor.

The strength of this collection is the cohesiveness borne of the interactions between its written and visual elements. Where transitions from one poem to another may feel abrupt (for example, when Goodwin leads her reader from the scene of a murder in “The Poisoning” to a surreal pageant in “Girl #4”), Proski’s prints provide a continuity of style, a familiarity of geometry that serves as a set of anchors for readers moving from poem to poem. The brilliant orange and shape of the cat in the print that accompanies “The Poisoning” is echoed in the construction of the crown bestowed on the speaker of “Girl #4,” the crown’s color is nearly identical to that of the animal, its peaks recalling the feline’s pointed ears. In the same print, the curved limbs that reach toward the representation of what the speaker called “the coin slot / wedged between my eyes,” harken to the sausage-shaped morsels on the plates in the print accompanying “The Poisoning,” just as the coins the limbs hold summon back the shapes of the plates themselves.

Conversely, Goodwin’s voice allows us to make sense of Proski’s more abstract scenes. In “The Exhibit,” she writes of “passing billboards” out the window, her speaker marveling, “Who knew Cracker Barrel / was a patron of the arts?” On the print opposite, Proski works in shades of black, gray, and inky blue that make discerning objects from the background quite difficult. Goodwin’s poem, crafted with quickly-passing images as seen through the eyes of her narrator, who watches her companion “roll down the window / lean out into the late light,” tells us what it is that we’re seeing: the sights that blur by in the night hours of road trips, such as watching as a sign emblazoned with “’Do you know JESUS?’ / rises out of the trees.” Without her poems, one could be forgiven for being unable to identify the rectangles as billboards, the central figure as the street.

In operating so successfully as a collaboration, Oracle Smoke Machine requires us to think of what we would be left with if its halves were considered alone, as whole in their own regard. How would we engage with Proski’s prints, the shapes and figures that often tiptoe along the line that separates legibility and inscrutability, the scenes that infuse the natural and domestic with whispers of sensuality and violence, without the guidance of Goodwin’s language, without the characters and context her poetry paints onto our experience of the scenes? What is one to think of Goodwin’s disparate lineup of speakers – the writer on the train watching her pen create “drags and leaps in blue,” the dancer at the techno club with her “hippie sleeves” and missing sneaker, the unprepared clarinetist who experiences rising panic as his big solo approaches – without the guidance of Proski’s images, which allow us to anchor our imaginings of the fantastical in the concrete and deepen our reading of Goodwin’s tone as color palettes slide along the spectrums of light and dark, as shapes overlap and obscure each other? It is rare that one encounters a collection of poetry that can be considered a truly interdisciplinary work of art. I can count on one hand the number of books I have read that employ such a serious commitment to the interplay between different artistic mediums as Christianne Goodwin and Stephen Proski’s Oracle Smoke Machine; I cannot recall, among the works that make up that short list of titles, any that were created in collaboration between two artists.

Whose contributions in Proski and Goodwin’s partnership serve as the oracle, spinning stories for the reader and foretelling from the divine? Whose work is the smoke machine, dealing in illusion and addition of drama, obscuring our vision of the truth and blurring suggestibility into belief? I doubt the answer to either of these questions can approach the intrigue of the combined mechanism as it exists in the book: the machine spewing prophecy with flair, the contraption programmed for an otherworldly performance.

::

Christianne Goodwin’s chapbook Oracle Smoke Machine is a collaboration with painter Stephen Proski from Staircase Books (Cambridge, MA). Her work has been published by Rust + Moth, The Lakeshore Review, Fahmidan Journal, and Panel Magazine. She is a graduate of the Boston University MFA program, the recipient of an Academy of American Poets University Prize, and a Robert Pinsky Global Fellow.

Stephen Proski (they/them) is a blind/disabled artist, writer, and advocate. Their work addresses their own personal experience of blindness and takes the form of painting, installation, text, and compositional objects that explore themes of precarity, vulnerability, and the blurry territory between legibility and illegibility. Their work has been shown in various venues in Kansas City, Boston, Chicago, and New York.

Annaka Saari is a writer from Michigan. She earned her MFA from Boston University, where she now works as the administrator for the Creative Writing Program. She also serves as managing editor for Solstice: A Magazine of Diverse Voices and a poetry reader for The Los Angeles Review. The recipient of a Florence Engel Randall Graduate Fiction Prize and a Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship, her work has been named a finalist for the Prufer Poetry Prize, longlisted for the DISQUIET Literary Prize, and appeared in or is forthcoming in The Southern Review, Pleiades, Image, Cleveland Review of Books, and other publications. Her website is annakasaari.com.

ID: Cover of Oracle Smoke Machine by Christianne Goodwin and Stephen Proski.