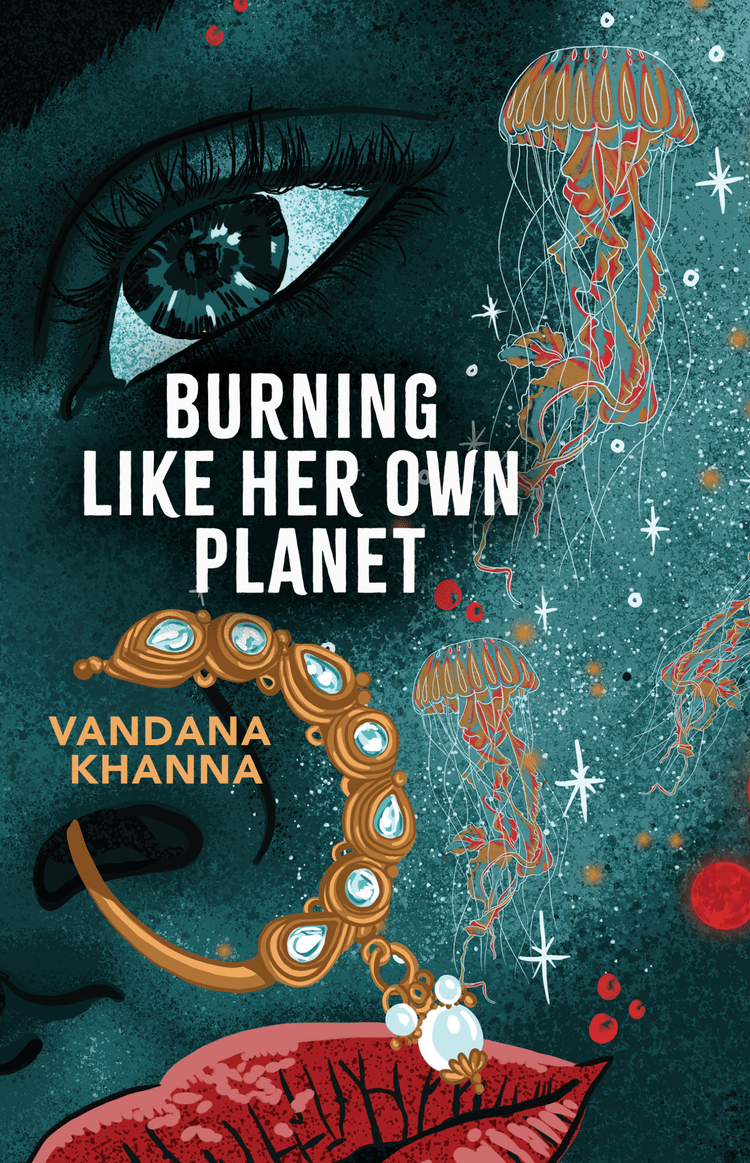

Burning Like Her Own Planet by Vandana Khanna

Review by Reyzl Grace

Alice James Books, 2023

::

When I was young, my father traveled frequently to Asia on business: Cambodia, Thailand, Bangladesh, taking with him questions I had not thought to ask and bringing back answers in the form of books and posters and statuettes, so that I learned the tales of Rama and Sita, of Radha and Krishna, right alongside those of Abraham and Sarah, of Isaac and Rebecca. Hence, when I—as a young, aspiring Jewish writer—first encountered some of the poems that now appear in Burning Like Her Own Planet in the pages of Diode over a decade ago, I took them to my heart immediately and have been a devoted fan of Vandana Khanna’s work ever since.

My appreciation for those pieces specifically—and for Khanna’s writing more broadly—has only been heightened by tasting them again, now steeped with the tightly curled leaves of the other forty-four poems in this, her third collection. As the book was released last April, much has already been said in other reviews about Burning’s sumptuously evocative phrasing, the glint and grit of its imagery, and the austere force of its narrative construction. Merely to repeat these things—to second the motion already resoundingly put forward by other critics that this is the work of one our most gifted writers in the most graceful sweep of her power, a book which draws on some of the most ancient motifs of South Asian myth-making to urge our reengagement with both the timeless and the contemporary terms of womanhood—would, at this point, be to damn it with faint praise.

I feel I can only do justice to Khanna’s achievement at this late hour by calling attention to something else in this book that has been less remarked. Throughout Burning, the journey of its speaker is reincarnationally refracted through the lives of Hindu deities and heroines. In a piece entitled, “Sita’s First Kiss with Suburban Landscape,” the legendary figure tells us that

In our seventh incarnation . . .

Our mouths meet in small disasters.

You taste of all the people you’ve already

been . . .

Sita’s experience—the inheritance of generations of South Asian women—informs and inflects the speaker, but the speaker brings something as well, as the title so deftly suggests. Through her, there is a newness in this experience that perhaps allows Sita an opportunity. It certainly gives one to the goddess Parvati who, in a poem titled “Parvati Rewrites Myth,” declares, “In this version, I’m done with kindness, // left it in my last life . . .”

The speaker seems aware, at times, that there will be some who balk at seeing myth rewritten. “Call me a faker,” she invites, “goddess-impersonator, dripping // in old gold and sweat” (“Name Calling”), but for the alert reader, this openness of myth becomes a sign of veracity. She starts a later piece by telling us that

This time, death finds me at the rough hem

of the forest, a numb wish of a girl in need

of a tether, a goddess with her new sores

stitched closed. (“Destruction Myth”)

We might question old gold, but which of us will argue with new sores? They are too bodily—too human—to elicit doubt.

This is one of the small miracles of this collection. The tight braiding of a mortal speaker—and especially an autobiographical one—with a mythic figure is often a means of sacralizing the human. In Khanna’s hands, it becomes a means of humanizing the sacred. Toward Burning’s beginning, in describing a childhood trip to India, Khanna relates how, as she shaped the sacred syllable OM, she was

trying

to make it sound like it was born in

my mouth, my third eye awake behind

the skull’s delicate cradle, blinking (“Hindu Mythology in Shorthand”)

and through all the vicissitudes of lifetimes, Khanna makes it seem effortlessly natural that, even as trial and heartbreak lend strength to the flame inside that girl, the delicacy of the human condition should spread to heaven, and a “Goddess in the Dark” (per the title) should

bow[] my head and practice[] how to hold

the moon’s broken bowl in my hands.

The silver sprigs of light slipping through

my woven fingers I mistake for holiness.

This interplay of holiness and fragility, dramatized so beautifully through the belief in reincarnation, is one of the many peculiar and wonderful parallels between Hindu and Jewish tradition. There are, for example, streams of Hasidic teaching which hold that, in addition to the process of gilgul, by which one’s soul returns to live again in another body, it is possible to receive an ibbur—the soul of another who joins with you temporarily, either to assist in the performance of some good deed or to share in the benefit of performing one. Even a revered ancestor or a great rabbi might come in this way to a very humble person if that person’s life affords the chance to do some good that their own lives did not have an occasion to accomplish.

This is what has kept me returning, again and again, for the better part of a year now, to Burning Like Her Own Planet. There are moments in all our lives when we are called to enter the innermost chambers of our own experience—those spaces that are holy among holies not by decree or according to the dictates of patriarchal propriety, but precisely because they are where generations of women with numb wishes and new sores and broken shards of moon have found some spark within them to “Wake from the tiger in your dreams / and with all the hands you are given, / pull at the thick, gold scruff of this world” (“Creation Myth”)—and it is a daunting thing, to say the least, to be called to those moments alone. But Khanna knows how to call down Sita and Radha, Durga and Parvati, and not only call them down but pull them up, push them across, draw them through to where they, in joining us, are joined by us too. Khanna brings us to a place where we can believe not only that they are present in the moment, but that that is as much a gift to them as it is to us.

Khanna’s writing is deeply rooted in her own cultural context, but in sharing that context as richly as she does she offers insight into the technique—she teaches us to invite the ibbur of Sarah or Rebecca, Rachel or Leah . . . any woman you might need or who might need you when

There’s not enough gold

in the world to make you feel holy, hallowed,

whole. No gloss pretty enough to save

a face marked by tragedy. (“The Goddess Tires of Being Holy”)

Yes. It is for this that I have kept this book by my bedside all these months—to remember that we need one another, and that, when we feel most alone, we are not.

::

Reyzl Grace is a poet, short story writer, and post-Soviet lesbian Jew from Alaska. Her work has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, named a finalist for the Jewish Women’s Poetry Prize and Best Literary Translations, and featured in Room, Rust & Moth, the Times of Israel, and elsewhere. By day, she is a public librarian in Minneapolis—by night, a poetry editor for Psaltery & Lyre and Cordella Magazine. You can find more of her at reyzlgrace.com and on Twitter/Bluesky @reyzlgrace.

ID: Cover of “Burning Like Her Own Planet” by Vandana Khanna