by Jonathan Frey

What awakened her that morning, years later? Not voices because he and the boy had been gone three days already. The last dawn cry of some night creature. Footsteps of cherubim across the floorboards. The mother dragged the quilt with her off the bed and went out the framed door to the steps and sat. The pine logs of the house the three of them shared were still fragrant and weeping pitch. At the bottom of the hill, the rest of the camp lay dormant. Some in half-made cabins and lean-tos, some still in tents, a loose assembly and the river beyond. All of this their small domain.

Now, looking out over it in the silver light of the predawn, her eyes went foggy with the gloss of vision, and the Lord showed her the two of them, the father and the boy, making their way up a narrow path. The boy carried the wood, and he carried the fire, and where was the lamb?

Then she knew. She knew what the Lord had told him. She saw it in his milky eyes as he looked off ahead toward a bald place on the ridge. He saw the place afar off, and he made his way toward it. The boy, beautiful and dutiful, followed.

She stood from the step and tore her housedress. Shoeless, she walked the house and the forest, wailing like a lost thing. One of the heldmen found her beside the river, making her way into deep water. Her feet walked the slick stones and then the soft mud as the cold reached between her legs, to her belly, the empty sac from which all that stupid hope broke forth. The heldman took her by the arm but she fought him, her fists to his face, her elbows to his throat, but he was stronger and carried her writhing back to the mud bank, and she thrashed there. The heldmen came around with their strange pale faces, wrong-shaped beards, and when she was still, they carried her back to her house on the hill and restored her to her bed, mud-crusted and breathless. The women ministered to her with broth and compresses, and the men stood watch so she would not escape again.

And there in her bed the vision returned to her. Her husband stood on the path to the bald. He beheld the place from afar. The boy was behind him carrying the wood. Where was the lamb? said the boy.

The Lord will provide the lamb, he said, and she bit down on her tongue so it bled. One of the heldwomen lay across her to hold her still.

“I see the place,” her husband said to her across the gauze of vision.

“What is the place? What use is the place to me? This is the place.”

“It is a great city.”

“It is a blood-marked city.”

He looked away toward the bald. Where was the lamb?

“Yes,” he said. “It is a blood-marked city.”

“Bring me back my boy,” she screamed, and the heldwoman pressed her to the mattress. She sprayed blood from between her teeth.

Later, the father and the boy atop the bald, flash of the knife.

When the heldwoman was asleep in the bed with an arm across her, she slipped from beneath, took fire from the iron stove, lit the hems of the bedclothes, the dried fringes of the skins, the knotted rug she had tied herself. The heldwoman woke screaming, and it took three of them to drag the mother from the house as the pitch hissed and caught.

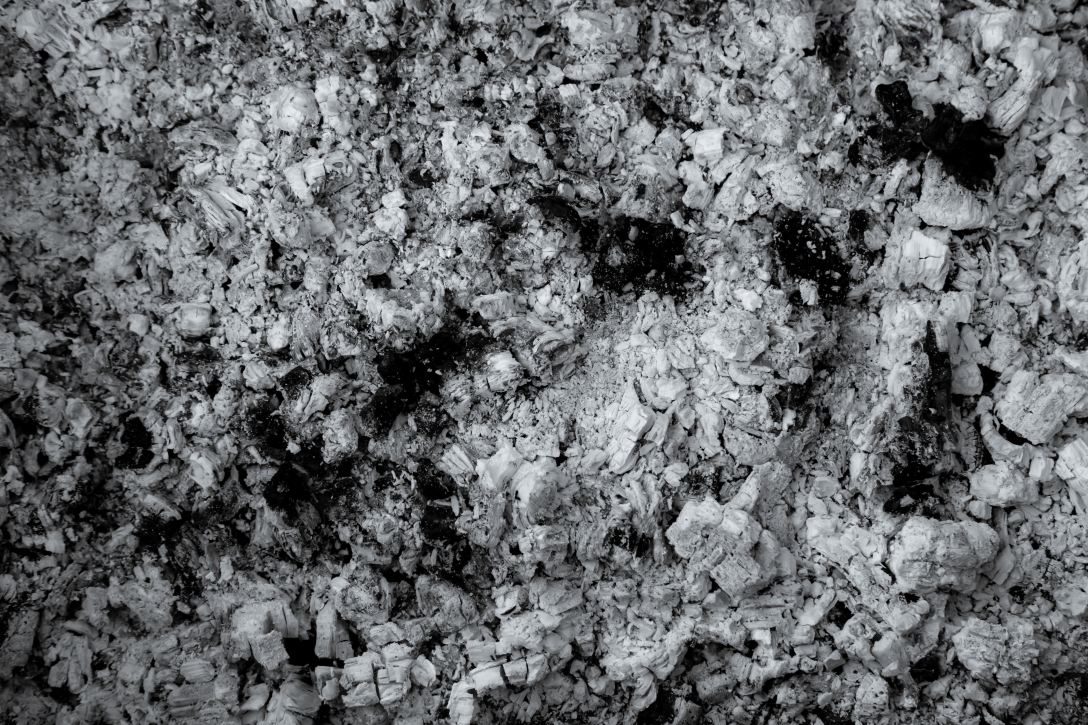

When he returned to her three days later with the boy, hale and whole, she was sitting among the warm ashes of the house. He went to her and held her, and the boy held her, and together they were still.

::

Jonathan Frey is associate professor of English at North Idaho College, teaching creative writing and composition. His work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Beloit Poetry Journal, The Millions, and elsewhere. He lives in Spokane, Washington, with his wife and daughters, and has just completed work on his first novel.

Image: Volodymyr Hryshchenko

ID: close up of ash from wood.