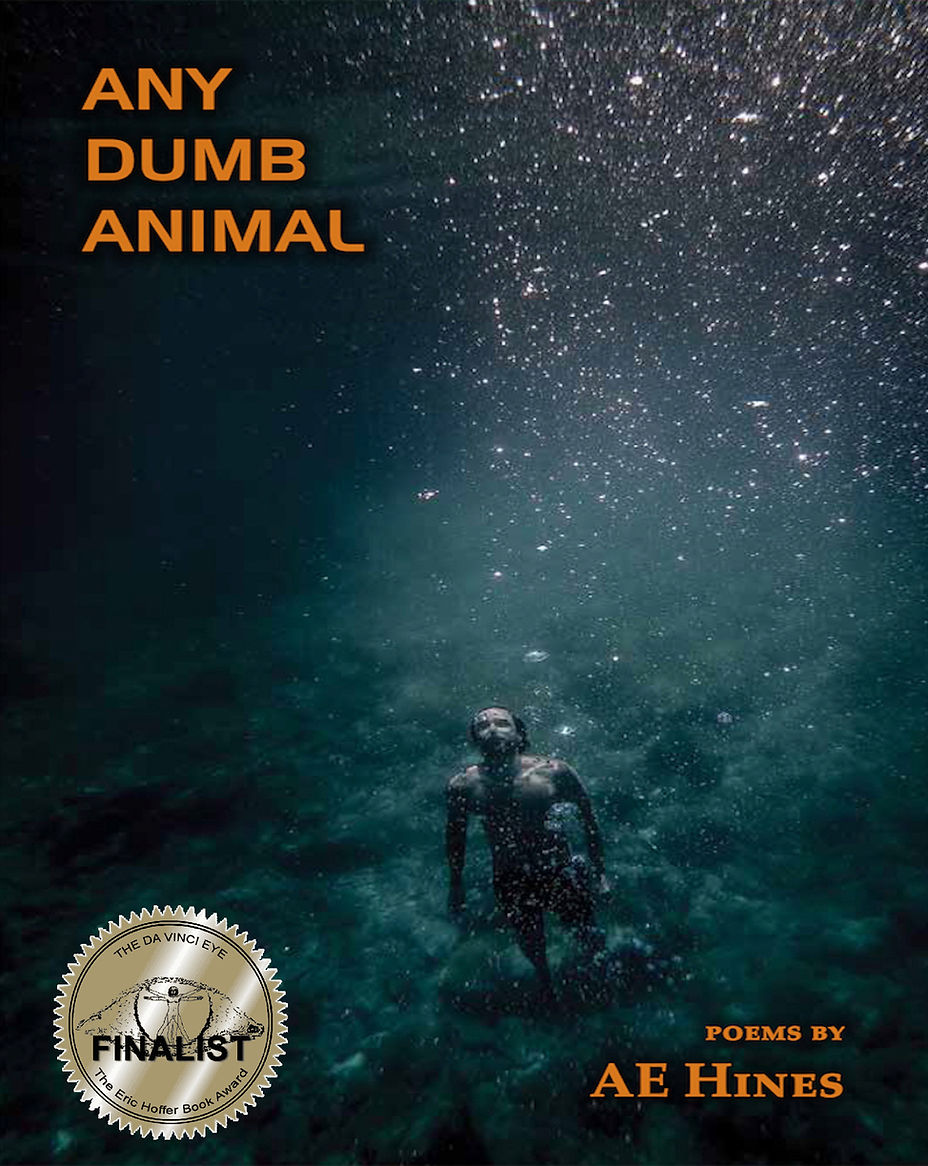

AE Hines’ autobiographical collection Any Dumb Animal (Main Street Rag, 2021) details his relationships with the men in his life. While the shadows of his homophobic, evangelical father and a similarly cold and detached ex-husband loom large, Hines goes on to find the beauty he deserves—in the arms of a loving partner, and in his young son. This lyrical memoir-in-verse is difficult to put down—an absolute must-read for generations to come.

Interviewed by Ana Pugatch.

::

AP: I’ve seen you read at a few events hosted by the NC Poetry Society, and your readings are truly captivating! Can you talk a little bit about when you started writing poetry, and your relationship to the poetry community?

AEH: We’re very blessed to have the NC Poetry Society, and I’ve felt so welcomed by the organization since returning to the state. I started writing poetry around 2014, when I was in my early 40s and still living in Oregon. Even though it’s now been almost a decade, I still feel like a relative newcomer to the world of poetry—perhaps because I came to writing late. In this regard, and as to your question about community, I have often said that being part of an active writing community is one of the most rewarding aspects of being a poet. For me, it’s probably second in importance only to the act of writing itself. Finding mentors and poetry friends in my early days— people I could support and who supported me—made all the difference. As artists, I think it’s imperative we show up and encourage each other, especially given the solitary nature of our work. It’s easy to become discouraged at times and question the value of what we’re doing.

AP: Your book is broken up into three sections: Revival, Regret, and Rebirth—each one starting with a different poem titled “Phone Call.” Can you tell us a little bit about the three “Phone Call” poems, as well as your organizing principle for the collection?

AEH: This is an interesting question. Given the autobiographical nature of the poems, I realized I needed some method for organizing and ordering them that would allow me to span thirty years of chronology, but without making the book feel sequential. While doing this, and looking over the three poems “Revival,” “Regret” and “Rebirth,” I decided I could exploit those words as themes for the book—symbolizing the repeating cycles we experience in our lives—and use those poems to divide the book into sections. This immediately created opportunities to order poems in more interesting ways. It was later, in realizing that I also had two poems called “Phone Call” that I decided I could write a third and begin each section with a poem of the same title. This echoed the type of repetition of life patterns I wanted. As you mentioned initially, much of the book explores my relationships with the men in my life—certainly my upbringing and relationship with my father, but also because of his influence, other relationships as well, particularly with my first husband, and our adopted son. The book also explores estrangement, and these phone calls—the crucial conversations they allow—become significant clarifying moments for the poems’ speaker (me), and act as a kind of milepost (and pseudo-chronological time) for the reader. The opening “Phone Call” poem, for example, takes place between my father and me while I’m in college, but then flashes forward to my divorce many years later. The second occurs in the midst of that divorce from my first husband but involves an incident with our then-young son. And in the final “Phone Call,” I’m again talking with my father, as the poem flashes backwards and forward in time, exploring my own decision to become a father myself.

AP: The title of your book comes from your father’s (rather callous) assertion that “any dumb animal” can learn how to swim—before throwing you into the water. Can you talk a little bit about how your fear of drowning serves an extended metaphor throughout the collection?

AEH: I nearly drowned in the ocean when I was very young—four or five years old— and if not for an alert older cousin, who noticed I had (without parental supervision) followed her into the water, I probably would have. I tried to learn to swim a few times, but when I was a teenager I nearly drowned again, this time in a river. A decade later, I did finally learn as an adult, long after I had developed a paralyzing fear of water. This was mostly due to the trauma my father inflicted on me throughout my childhood in his ill-conceived attempts to force me, as if magically, to start swimming. “Any dumb animal,” indeed. My father was an emotionally and physically abusive man, and this marked me as a child. I was terrified of him, and quite literally slept with one eye open. Taunting me with water and possible drowning was just one of the games he liked to play. So, in my case, the metaphors—of trying to stay afloat, of treading rough emotional waters, and so forth—come all too naturally. Even today, whenever I have or think of an emotional situation that feels overwhelming, I get this sense of being tossed about by the sea, and sucking water into my lungs as my legs kick frantically. Of course, I can’t say I set out to write about any of this in advance. I didn’t. These are simply the poems that came from wherever in the mind poems come.

AP: “My Father’s Son” ends with the description of a photograph: “the memory of the boy he had seen through the lens / so much better than the real thing standing / there before him.” Can you share your thoughts about the dichotomy of reality and memory? How might poetry serve as a vessel for our memories of the past?

AEH: This poem, for me, seems to be about the limits of our memory, and how our brains have evolved to ensure our survival. Our conscious minds seem to be mostly pattern-recognition devices, and they often predict the worst. We’re more likely to survive if we see a snake lying in the grass and instinctively jump back, rather than to assume it’s only a shadow or stick (which it most often is) and ignore it. This poem opens with “If my father was ever tender, I don’t remember.” And later says: “Biology has blessed us with the strongest recollection / for what to avoid…” Or put another way, while I am holding open in this poem possibility for my father—that there were good times and tender moments that my memory has failed to retain—I also recognize that early on, I learned I was not safe with him. He couldn’t be trusted. This seemed necessary for my own survival. The surprise for me, in writing this poem, was the conclusion that you referenced—which is also where the title of the poem originated. “My Father’s Son,” in this case, is not me. It’s that photo he cherishes, the faulty memory of a little boy he carries around with him, the man he imagined the boy would become. His memory is all that remains of that imaginary boy, and it doesn’t resemble the man I grew into, the one my father ultimately rejected.

AP: History tends to repeat itself—but you make a conscious decision to break the cycle: “I will never let [my father] into these hands. My son, never the least bit afraid.” How much does the past shape who we are—and how much agency do we have in deciding our own future?

AEH: Interesting question. In my view, the past shapes us into who we become, and will steer our lives in the present, more or less unconsciously, unless we spend the time necessary to look at it objectively and let go of patterns that no longer serve us. For me, this entailed a lot of therapy, the trial and error of medication, and decades of journaling. It also required me to admit patterns from my childhood that I repeated (and allowed to repeat) with my first husband. In terms of agency, I’d like to say that we have full agency to decide our own futures. And while some part of me truly believes this, another wants to admit that what we are given at birth (by virtue of our genetics) and as children (through our upbringing) will impact us our entire lives. I think the key is self-awareness and compassion—which includes having kindness and patience for ourselves, however we show up. You know, while not to excuse him, I couldn’t have examined my own father’s treatment of me and the coping mechanisms I developed to survive, without also appreciating the type of childhood he must have had. Perhaps, he did far better with me than his own father had? That’s a frightening prospect. But it is, as you say, a cycle. And while I made conscious decisions with my own son to change those harmful patterns, I’m also self-aware enough to know that I made plenty of mistakes. And try as I might, I will continue to do so. Parents protect and nurture. But we also, unwittingly, do harm. So, compassionately, I can allow that my father was a broken person, but still not excuse his abuse. I realize I have to hold out this compassion because there are plenty of ways I must have failed in my own parenting. Who knows, maybe my son will write a book!

AP: Your collection also provides a window into the South’s history of homophobia—starting in adolescence, to the AIDS epidemic, all the way to filling out a school form for your son and having to decide “which father to list as his mother.” Looking back, how far have we come in terms of American society’s acceptance of the LGBTQ+ community?

AEH: You know, having recently returned to the South after more than thirty years, it’s wonderful to see how much better things are than they were when I was a kid. There’s more awareness and acceptance, certainly. And nationally, we have a few more legal protections. We can marry who we love—at least for now. Because at the same time, I’m deeply troubled by the current trend of ripping away civil liberties, and especially, the vilification of members of our transgender community. I’m concerned about the trend of restricting speech in schools, banning books, and targeting children by making illegal gender-affirming healthcare. There’s also this recent obsession with banning Drag performances all over the country—as if make-up, dresses, and high heels, are suddenly some sort of threat? Do politicians really think they can simply legislate members of our society out of existence? I guess what they really fear is tolerance. Tolerance is the real threat because tolerance doesn’t divide.

AP: Any Dumb Animal is your debut collection. How has your current MFA program at Pacific University shaped your craft, and what does the future hold for you in terms of new projects?

AEH: I joined the Pacific MFA program because of specific faculty I wanted to study with, and it’s been a wonderful experience. While my first book was already coming out, I had a strong desire to deepen my writing practice, and more formally study craft. Engaging with these artists and building a wider community of writers has positively influenced my own writing, in ways that are difficult to overstate. I’ve definitely expanded the range of craft skills I can call upon in my own work, especially in the revision process. My own palate as a reader—my appreciation for the work of others—has likewise been enriched. And I’ve learned to generate more work in a compressed time period, which can help me shut up that internal editor who likes to criticize and tell us not to tell the truth as we’re writing. Shutting him up can lead to some genuine, surprising discoveries. One of which was the theme for my second book. I’m really excited about it, and very focused editing the manuscript as we speak.

::

AE Hines grew up in rural North Carolina. Any Dumb Animal was a daVinci Eye Finalist and received an Honorable Mention in the 2022 Brockman-Campbell Book Contest. His poetry has been published in Rattle, Alaska Quarterly Review, The Southern Review, Rhino, Ninth Letter, and The Missouri Review, among other journals. You can find more of his work on his website, https://www.aehines.net.

Ana Pugatch is a poet from Massachusetts. She was the ’20-’21 Heritage Fellow at George Mason University, and her thesis, Engrams: Seven Years in Asia (Redhawk Publications, 2023), won the Lena Shull Book Award. She now lives in Raleigh, NC with her husband and son.

Image description: Cover of Any Dumb Animal, poems by AE Hines.